By the Numbers: 128

The total number of high-tide flood days observed in Annapolis, Baltimore, Norfolk and the District of Columbia last year

The Chesapeake Bay has more than 11,600 miles of shoreline. Evidence of its changing tides can be observed along much of the region, whether it is a high water mark on a dock piling, a line of seaweed on a beach or a shorebird pulling shellfish from the mud of a temporarily exposed flat.

In some watershed cities—like Annapolis, Maryland—the difference between high and low tides is about one foot. In others—like Norfolk, Virginia—this difference can reach up to three feet. We have built our roads, homes and buildings around the regular movement of this water. But as sea levels rise, land subsides and natural barriers to coastal flooding are lost, our coastal cities will face more impactful high-tide flooding that occurs regardless of heavy winds or rain.

High-tide flooding has also been called sunny-day, shallow coastal or nuisance flooding. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) records a high-tide flood when one of its local tide gauges measures a water level above the local threshold for minor impacts. While the depth and extent of high-tide floods can vary, the nuisances that result are far from minor: disrupted transportation, degraded stormwater management systems, flooded roads, homes and businesses, and strained maintenance budgets.

Rates of high-tide flooding on all coasts are rising. In a June 2016 report on the state of high-tide nuisance flooding in the United States, NOAA researchers attribute increasing flood frequencies to local sea level rise—which itself is attributed to the melting of ice on land as the air warms and the expansion of seawater as oceans warm—and local land subsidence, or the settling or sinking of land. Indeed, according to the report, “annual flood rates have increased locally by two or three times or more as compared to the rate experienced 20 years ago.”

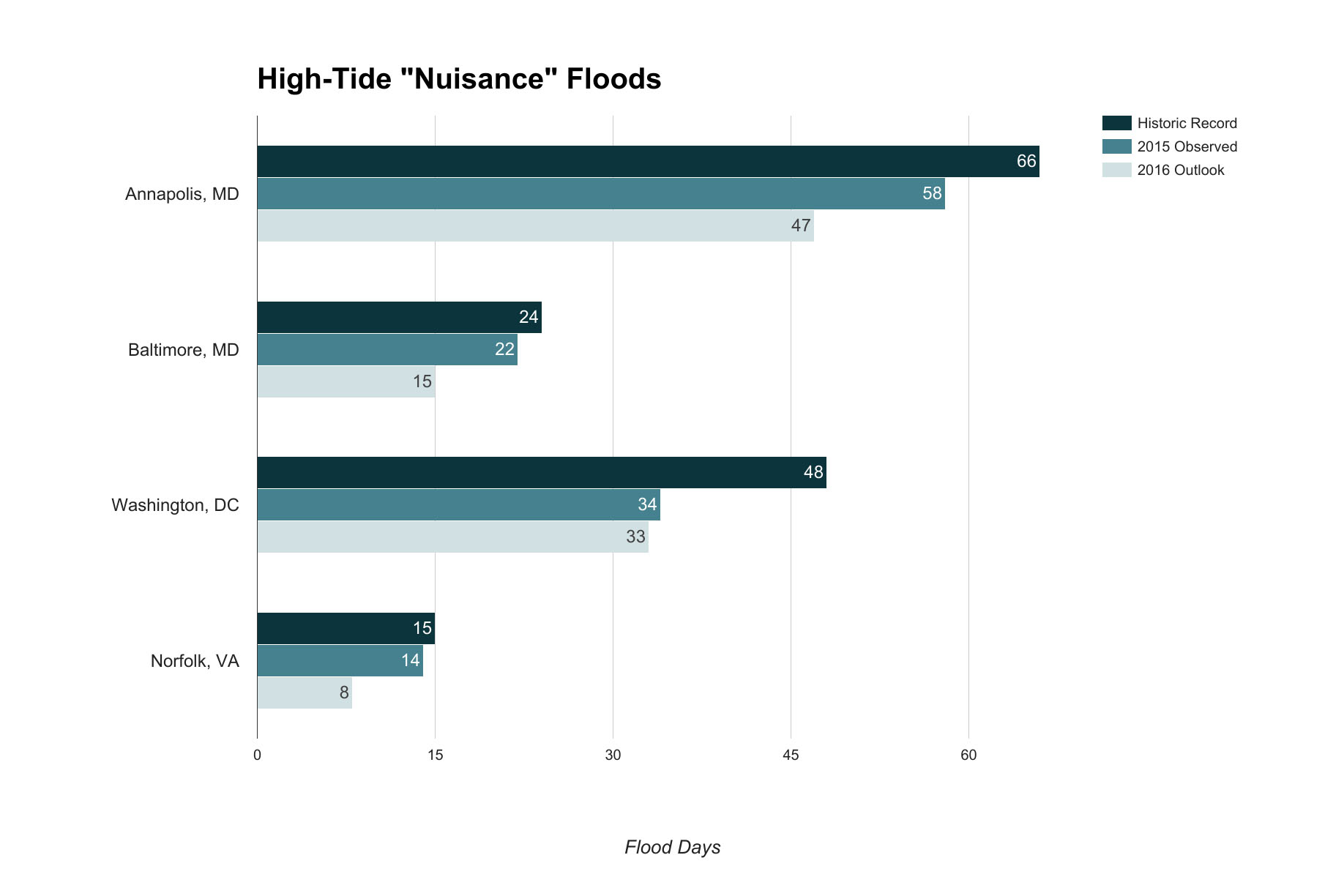

Of the 28 local long-term tide gauges operated by NOAA, four are in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Together, these four cities—Annapolis and Baltimore in Maryland, Norfolk in Virginia and the District of Columbia—experienced a total of 128 high-tide flood days in 2015, with Baltimore and Norfolk experiencing local totals just two days and one day below the highest historical record. These floods were likely exacerbated by El Niño, which affected winds and storm tracks along the mid-Atlantic and West coasts.

The 2016 outlook for each of these four cities is lower than the number of flood days the cities observed in 2015: 15 flood days are expected to occur in 2016 in Baltimore, 47 in Annapolis, 33 in Washington, D.C., and 8 in Norfolk. However, NOAA expects future outlooks to underestimate flood days because of the increasingly “nonlinear response” flood frequencies will have to sea level rise. Furthermore, the agency’s high-tide flood outlook does not account for flooding compounded by local rainfall, and precipitation in the watershed is expected to increase in response to climate change.

While we cannot reverse the effects of climate change that have already been observed in the region—which include warming temperatures, rising sea levels and more extreme weather events, as well as coastal flooding, eroding shorelines and changes in the abundance and migration patterns of wildlife—we can enhance our resiliency against them. To build resiliency against high-tide flooding, for example, cities have relied on flood barriers to block rising water, drafted ambitious plans to raise low-lying streets and constructed new facilities higher off the ground.

Through the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, the Chesapeake Bay Program has committed to increasing the resiliency of the region’s communities, living resources and wildlife habitats to the adverse impacts of changing environmental conditions. Learn about our work to monitor and assess the trends and impacts of climate change and to pursue, design and construct restoration and protection projects that will enhance the resiliency of our ecosystem.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories