From trash pit to amphibian oasis

Forest Pools Preserve protects a spring phenomenon for frogs and salamanders

In late March, Pennsylvania’s South Mountain was already weeks into spring’s thaw, but a stinging breeze and sinking sun meant jackets and beanies for a group forming under the tall, swaying pines near Kings Gap State Park.

Devin Thomas, almost ten years old, from nearby Carlisle, showed up in shorts and sneakers but came prepared with a headlamp he made using an old pair of underwear and faithfully equipped with enthusiasm for the outdoors.

“He won’t even kill bugs,” said Ray Thomas, Devin’s father—also wearing shorts.

As more people arrived, they took turns dunking their boots in a bucket of soapy disinfectant, used to get rid of harmful microbes, seeds, and any other invasive species. It was a precaution justified by the group’s destination, the vernal pools of Forest Pools Preserve.

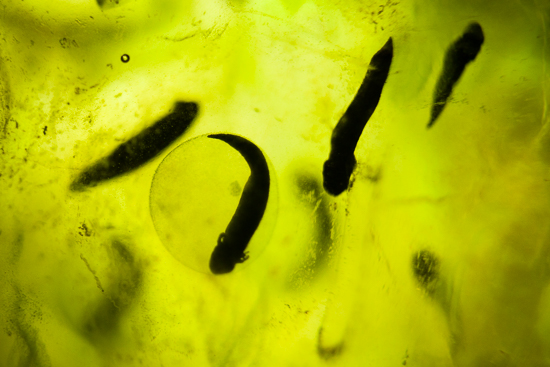

Vernal pools are ephemeral forest ponds, fed by snow, rain or groundwater, and blanketed in leaves from a healthy forest. They host a wealth of animals and only stay wet for about seven months, which is just long enough for a cascade of frogs and salamanders to use them as a home for their developing young.

You won’t find fish—they would eat all the eggs—but if you get the timing right, you’ll hear the clucking chatter of spawning wood frogs or the car alarm call of camouflaged spring peepers. You might see yellow spotted salamanders wriggling among the leaves, and you might see tiny fairy shrimp, the country cousins of the commercial pet Sea-Monkeys.

If you were visiting the area ten years ago, you would also see piles of trash and hear the sound of broken glass underfoot.

“I guess back in the olden days you would see these depressions in the forest, and before we had trash pickup I think that’s where a lot of people would just put their trash,” said Molly Anderson, a volunteer program manager with The Nature Conservancy. “You’d walk and you’d just hear ‘crunch crunch.’”

The Conservancy purchased the preserve’s 70 acres in 2007, and for three years it held volunteer trash cleanups and monitored the vernal pools there. A Conservancy scientist started noticing that some of the pools weren’t holding water long enough for the young amphibians to develop.

Several theories arose. One was that growing development, with people drilling wells, had lowered the water table below the groundwater-fed pools. Another was that it might be just be a naturally drier period than normal.

“I also heard that maybe the clay liner that was holding the water, that it was popped by all the trash that was laying in it,” Anderson said.

In 2010, with grants received by the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy held a workshop to restore some of the ailing pools. Volunteers Mike Bertram and Kathy King, a local married couple, were instrumental volunteers overseeing the effort, and nearby Dickinson Township provided equipment, Anderson said.

The work involved raking away leaves, setting aside mosses and other plants, using heavy machinery to remove layers of soil and carefully replacing everything above a synthetic liner placed in the depression. A season’s worth of leaf litter was the finishing touch.

“The restoration took place in the beginning of August, and we came back in the fall of the same year and it was hard to tell that anything was done there,” Anderson said.

In the years since, the restored pools hold water when the pools that weren’t restored are drying up, Anderson said. Now Forest Pools Preserve serves not only as critical habitat but as a means to raise awareness.

“One of the things that we’re concerned about is that because vernal pools are really small and kind of unnoticeable, they’re not protected really under any kind of laws protecting water,” Anderson said.

Anderson said the Conservancy is trying to educate local governments about the importance of vernal pools and address issues raised by landowners, such as the threat of mosquitos. Aiding the effort, the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program has a vernal pool landowner incentive program and an online registry.

“In a really healthy vernal pool, you’ll have a lot of different predators on mosquito larvae that would keep the mosquito numbers in check,” Anderson said.

Conservancy volunteer Andy Green helps monitor the pools and led the walk that the Thomas family attended. A retired doctor who grew up in Carlisle, Green managed remnant prairie and stormwater programs in Illinois before returning to Pennsylvania. He lives just down the road from Forest Pools Preserve.

“It’s interesting, there are none of these pools in the North Mountain, or many of these mountain ridges north of here,” Green said. “This is essentially a South Mountain phenomenon.”

Bringing the group to a pool fed by groundwater, Green pointed out the telltale masses of wood frog eggs. Wood frogs love a 40-degree night with rain, he said. The eggs were a sign that the frogs had already found a break in the cold weather, came, and left before anyone could spot them.

“They fooled everybody,” Green said.

Smaller in number were masses of eggs belonging to Jefferson and spotted salamanders, attached to sticks where the male of the species first places a sperm packet, or spermatophore.

As the adults listened to Green, the younger members of the group dispersed once they learned that they could find salamanders underneath rocks. They became the most avid explorers of the night, flipping rocks and logs, finding tiny red-backed salamanders, and replacing them as they were—at Green’s urging—before moving on to crouch low and face the water’s surface at each pool.

At the site of another pool, Green was dismayed to find nothing but a depression full of leaves. Under some of the leaves were wood frog egg masses, still moist, but the pool protecting them had dried up, and without a rain the eggs would dry up as well.

Green led the group to a final stop just over the boundary with Kings Gap State Park, which the Conservancy acquired in 1973 and transferred to the state. The sound of spring peepers became louder and louder as the group approached a pool, until the chorus seemed to be coming from every direction at once.

One of the adults held a spotted salamander she had found near the pool, showing it to the admiring group and periodically wetting her hands in the pool to keep the salamander’s skin moist—just another measure to keep the vernal pool community healthy.

The peeper’s call that had been so piercing faded quickly as the group left the low-lying bowl holding the pool, giving way to the crunching of leaves and excited recounting of what the group had just seen.

To view more photos, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Flickr page

Photos and text by Will Parson

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories