The Watershed

What is the Chesapeake Bay watershed?

The Chesapeake Bay watershed is a large area of land that drains into the Chesapeake Bay. It spans more than 64,000 square miles and is home to more than 18 and a half million people. It provides habitat to more than 3,600 species of plants and animals, and includes forests, farms, and rivers and streams, as well as small towns, expanding suburbs and large urban centers.

The Chesapeake Bay watershed has the largest land-to-water ratio of any coastal watershed in the world, in large part because the Bay itself is surprisingly shallow. This means that what we do on the land has a big impact on the Bay, and managing the health of the watershed as a whole is critical to maintaining the health of the Bay and the people that depend on it.

What rivers flow through the Chesapeake Bay watershed?

Hundreds of thousands of creeks, streams and rivers flow through the Chesapeake Bay watershed. These tributaries send fresh water into the Bay, provide food, water and shelter to wildlife and offer people places to fish, boat and swim. Virtually every resident of the Chesapeake Bay watershed lives within a half-mile of at least one tributary that eventually drains into the Bay. The region’s largest rivers, in order of size, are the Susquehanna, Potomac, James, Rappahannock, York, Patuxent, Choptank, Nanticoke and Patapsco.

Major rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Susquehanna River

New York, Pennsylvania & Maryland

The Susquehanna River begins in Cooperstown, New York, and flows over 440 miles before reaching the Chesapeake Bay at Havre de Grace, Maryland. The longest river on the East Coast, it supplies about half of the freshwater that flows into the Bay. While it is challenged by agricultural runoff, efforts to plant streamside trees and install on-farm conservation practices are helping reduce pollution.

Potomac River

West Virginia, Maryland, Virginia & Washington, D.C.

The Potomac River flows about 405 miles from its source in West Virginia until it enters the Chesapeake Bay at Point Lookout, Maryland. Its unique features include Great Falls—a series of waterfalls and rapids that marks the transition from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain—and double water gaps—where the river cuts through two different ridges of the Blue Ridge Mountains. While the river faces challenges from industrial pollution, wastewater overflows and urban stormwater, its health is improving.

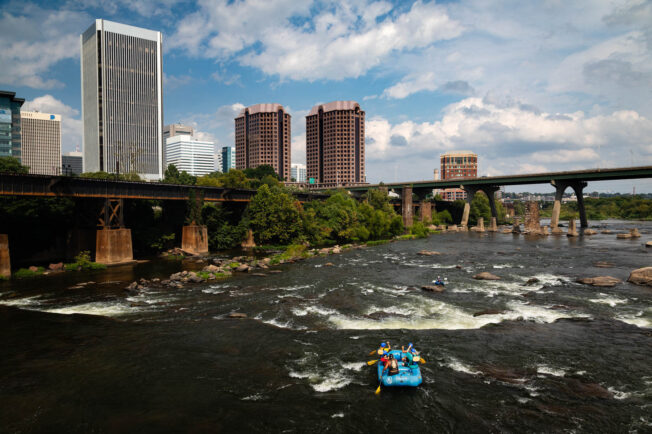

James River

Virginia

The James River flows about 348 miles from the Appalachian Mountains to its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay in Hampton Roads, Virginia. A series of iconic waterfalls run through the commonwealth’s capital, creating the only place in the United States where extensive whitewater runs through a major urban center. While Virginia’s largest river faces challenges from agricultural runoff, wastewater overflows and urban stormwater, its health is improving.

Rappahannock River

Virginia

The Rappahannock River flows about 195 miles across Northern Virginia. Near Fredericksburg, it transitions from a shallow and rocky stream to a deep, slow-moving river. While its watershed is primarily rural and forested, population growth and rapid development are increasing pollution and placing stress on water supplies. It has been named one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers.

York River

Virginia

The York River begins where the Mattaponi and Pamunkey rivers converge and flows about 34 miles before reaching the Chesapeake Bay near Yorktown. While its watershed is dominated by forests, farms and wetlands, population growth and rapid development are paving green space and compounding widespread shoreline erosion. Efforts to install living shorelines and restore oyster reefs are helping protect the river.

Patuxent River

Maryland

The Patuxent River flows about 115 miles from the hills of the Maryland Piedmont to Drum Point. It is the deepest tributary in the Chesapeake Bay watershed and the largest river entirely within Maryland. While it faces challenges from agricultural pollution and development, its lower estuary is home to the Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary, which protects over 1,700 acres of tidal wetlands to support research, education and recreation.

Choptank River

Delaware & Maryland

The Choptank River flows about 65 miles from Choptank Mills, Delaware, until it empties into the Chesapeake Bay between Blackwalnut and Cook points. It is the longest river on the Delmarva Peninsula, and one of the most productive blue crab nurseries in the Chesapeake Bay. While it is challenged by agricultural pollution and a decline in underwater grasses, efforts to restore oyster reefs, wetlands and water quality are helping protect the river.

Nanticoke River

Delaware & Maryland

The Nanticoke River flows about 64 miles from its headwaters in Kent County, Delaware, until it empties into Tangier Sound. It is the largest Chesapeake Bay tributary on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and the most pristine river in the watershed. While it faces threats from development, habitat loss and sea level rise, local partners have protected over 3,400 acres of land in its watershed, and it continues to support rare, threatened and endangered species.

Patapsco River

Maryland

The Patapsco River flows about 39 miles from Marriottsville, Maryland, to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. The 2018 removal of Bloede Dam in Patapsco Valley State Park opened 65 miles of the river to the movement of migratory fish and created a rocky rapid for kayakers. The river is challenged by nutrient and sediment pollution, fecal coliform bacteria and toxic contaminants.

How does geology shape the Chesapeake Bay watershed?

During the last Ice Age, mile-thick glaciers stretched as far south as Pennsylvania, and the Atlantic coastline was about 180 miles farther east than it is today. Approximately 18,000 years ago, these glaciers began to melt, carving streams and rivers that flowed toward the coast. Rising seas eventually submerged the area that is now known as the Susquehanna River Valley, and this drowned river valley became the Chesapeake Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay assumed its present shape about 3,000 years ago. While the Bay itself lies within a physiographic province known as the Coastal Plain, its watershed includes parts of the Piedmont, Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, and Appalachian Plateau. The waters that flow into the Bay have different chemical identities depending on the geology of the place they originate.

Coastal Plain

The Coastal Plain is a flat, lowland area with a maximum elevation of about 300 feet. It extends westward from the continental shelf to a fall line that ranges from 15 to 90 miles west of the Bay. Waterfalls and rapids clearly mark this line, which is close to Interstate 95. Cities like Baltimore, Maryland, Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Virginia, were built along the fall line to take advantage of the potential water power generated by the falls.

Piedmont

The Piedmont ranges from the fall line westward to the easternmost ridge of the Appalachian Mountains. Over time, weathering and erosion have smoothed the province into gentle, rolling hills. The Piedmont contains important natural resources, such as granite, marble and coal. The nation’s first commercial coal mine was opened in 1701 near Richmond, Virginia.

Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, and Appalachian Plateau

The Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, and Appalachian Plateau are characterized by mountains and valleys, and are rich in coal and natural gas. They are also known for their scenic beauty, from the sweeping views along the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the narrow water gaps in the Lebanon (Pennsylvania), Shenandoah (Virginia) and Hagerstown (Maryland) valleys.

How are we protecting the Chesapeake Bay watershed?

In a watershed, pollution that occurs upstream finds its way downstream. This means that to protect the Chesapeake Bay, we need to protect clean water and valuable landscapes across the entire watershed. The Chesapeake Bay Program is a watershed-wide partnership that brings together federal, state and local leaders, academic institutions and community groups to accelerate progress toward science, restoration and conservation, and to preserve the Bay’s ecological, cultural, economic, historic and recreational value for the people who live, work and play in the region.