Haunted by the ghosts of forests past

Rising seas cause inland migration of marshes

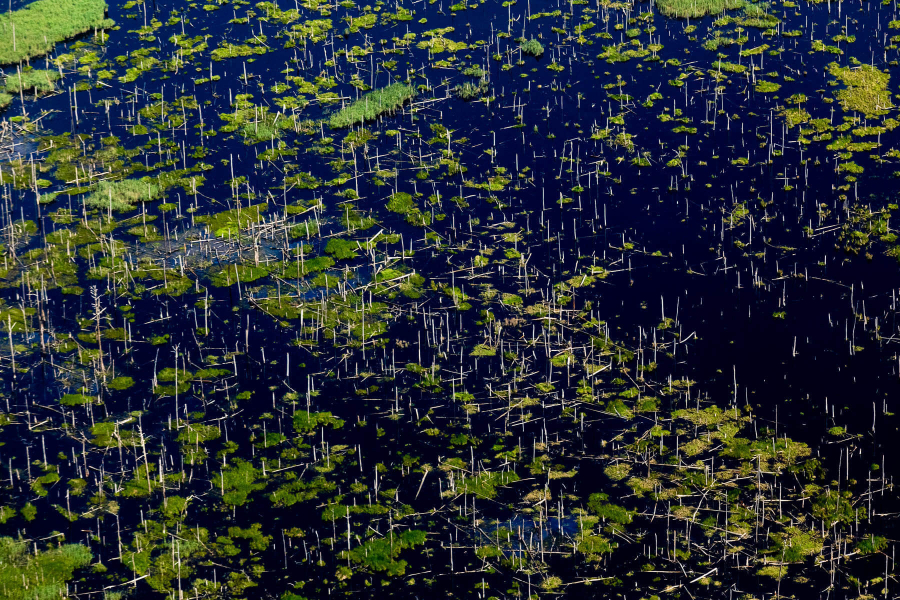

It starts with the hardwoods. The loblolly pines are next to go. These stands of dead trees, bare and pale, are becoming a much more common sight in the Chesapeake. “Ghost forests” aren’t a setting for spooky Halloween tales—they’re a stark reminder of how the changing climate is affecting our landscape.

All along the Atlantic coastline, trees are dying off in large numbers as rising sea levels cause wetlands and salt water to move farther inland. While this process is something that has occurred for thousands of years as a part of natural environmental changes, it’s now happening more quickly due to climate change.

The Chesapeake region is particularly vulnerable to this kind of landscape-scale alteration. As the continental crust north of here rebounds from the weight of immensely heavy glaciers, the Chesapeake region is sinking accordingly—a process called subsidence. Because seas are rising at the same time the land is sinking, water levels are increasing here at approximately twice the global average rate.

A study out of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science suggests that since 1850, more than 100,000 acres of forested lands along the Chesapeake Bay have transitioned to marshland. Since the 1930s, the rate of inland marshland migration has more than quadrupled.

Effects of marsh migration

While the sight of hundreds of dead trees may seem terrible for the environment, researchers caution that nature is rarely so black and white. The change from forested land to marsh land can have a variety of effects, both positive and negative.

On one hand, forests are critical to the Bay ecosystem. They protect clean air and water, provide habitat for wildlife, store carbon, and support recreational activities and the region’s economy. When forests are destroyed or fragmented, those ecological services and economic benefits are lost. To keep the Chesapeake watershed healthy in the face of continuing pollution, researchers estimate that 70 percent of the region needs to be forested, so it’s vital that we protect these ecosystems.

On the other hand, salt marshes are also extremely productive and valuable ecosystems. These wetlands provide habitat for hundreds of species, trap and filter pollutants, and can slow storm surges to limit inland damages from storms and flooding. In this way, they can help increase the inland area’s resilience to the effects of climate change.

Because there is little we can do to quickly stop sea level rise, in many places, it’s often a matter of understanding the processes that are taking place and working with them to get the best possible results. Here in the Chesapeake, this means ensuring that marshes can migrate in a sustainable, environmentally-friendly way.

Planning for the future

One of the best places in the region to see ghost forests is the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. Matt Whitbeck, a biologist who has worked at the refuge since 2008, says, “People can come and see with their own eyes. The evidence of sea level rise is everywhere. Areas that were hardwood forests when I arrived are now standing dead trees with marsh underneath.”

Within the refuge, approximately 5,000 acres of marshlands have been lost since the 1930s, transitioning to open water as a result of sea level rise, subsidence and widespread habitat alteration by nutria, an invasive rodent that can completely clear the vegetation of a wetland. Over the same period, just under 3,000 acres were converted from forested uplands to new marsh. The rate of marshland loss is greater than the rate at which forested lands are transitioning to marshes, leading to a net loss of these vital marsh ecosystems.

Whitbeck is collaborating with partners like The Conservation Fund and Audubon Society to protect the refuge’s wetlands by working with marsh migration processes. Rather than the traditional conservation approach of simply protecting current marshlands, they are working to identify and protect the areas where marshes may migrate and be likely to persist in the future.

The team worked with computer models to envision how the landscape would look at the end of the century and compiled their results in the report “Blackwater 2100: A Strategy for Salt Marsh Persistence in an Era of Climate Change.” By 2100, an estimated 90 percent of Blackwater’s current high marsh wetlands, which are characterized by irregular flooding, may turn to open water. Unlike low marshes, which flood twice each day, high marsh wetlands are important nesting habitat for several species of birds.

Based on analysis of the models, there are two potential areas where the marshes could migrate: to the eastern end of the refuge, near the Nanticoke River; and the western end of the refuge, around Coursey Creek. Keeping these areas open to marsh migration could help to ensure the survival of the wetlands, but much of the land is not currently set aside for conservation.

Strategies for wetland preservation

Conserving land for future marsh migration isn’t the only strategy conservationists are employing to help ensure the future of the wetlands: they’re also tackling invasive species. Marsh transition zones are particularly susceptible to phragmites, an invasive grass that can quickly colonize the area. Unlike native marsh plants, phragmites provides very poor habitat for birds like the black rail, saltmarsh sparrow, seaside sparrow and clapper rail that rely on Blackwater’s tidal marshes. Managers are targeting phragmites in the transition zones with herbicides to prevent it from establishing and taking over.

Another strategy is to remove some of the dead and dying trees. Because these trees are potential habitat for predators like owls, salt marsh birds tend to avoid them. By removing the trees, managers can increase the amount of habitat available to the marsh birds.

Managers are also trying to use salt-tolerant grass species, such as switchgrass, to perform some of the ecosystem services that would have been previously provided by agricultural crops. The grasses can trap nutrients and sediment and stop them from entering waterways. Stands of switchgrass can also provide an easy transition zone for salt marsh grasses like cordgrass.

By employing all of these strategies, managers hope to preserve Blackwater’s tidal marshes and the species that depend on them. You can do your part to protect wetlands by reducing the amount of pollution that can run off your property: install a rain barrel to capture and absorb rainfall, use porous gravel or pavers in place of asphalt or concrete, and redirect downspouts onto grass or gravel instead of paved driveways or sidewalks. Learn more about the importance of wetlands in the Chesapeake.

Comments

I have recently become alarmed at the acceleration rate of our loss of habitat and trees as well. So much so that I want to do something about it to help in the way of plantings for new growth whether it would be switch grass or better trees. Can you recommend anything in particular?

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories