In wake of flooding, Ellicott City works to recover and adapt

In months since devastating flood, the historic town has remained resilient

The sound of a phone echoes through three empty floors of a restaurant under construction. Michel Tersiguel’s steps crinkle plastic sheeting on the ground as he walks past stacked tables and empty shelves to the phone hanging on the wall of the entry hallway. His face lights up, “Our phones are working! That’s the first time I’ve heard it ring.” For the first time since floods on July 30, 2016, pummeled historic Ellicott City, Maryland and forced his business, Tersiguel’s French Country Restaurant, to close for repairs nearly two months ago, he picks up the phone to say, “Bonjour, Tersiguel’s, may I help you?”

The Flood

At 7:18 p.m. on Saturday, July 30, the National Weather Service issued a flash flood warning as a thunderstorm lumbered east across Maryland. Runoff coursed through the many tributary streams of the Patapsco River that carve down steep slopes around historic downtown Ellicott City.

Walls of water swept down driveways, streets and parking lots in downtown Ellicott City; it filled basements and first stories of buildings and launched cars into shop windows. At some point the bank of a retention pond at the Burgess Mill Station residential development breached, sending the water it was containing careening downhill towards Main Street. Just over six inches of rain fell in only two hours and by 9:00 p.m. the Patapsco rose 13 feet, turning a normally serene river into a tree uprooting, bank-eroding, debris-carrying monster for miles.

Heroic citizens rescued a woman from her car on Main Street as the water surged around them, but tragedy visited the historic downtown area as well. Jessica Watsula, mother to a 10 year-old, left Portalli’s Italian restaurant after a night out when she was caught in the wall of water that had taken over Main Street. She was swept away and killed by the surge. Joseph Blevins and his girlfriend, Heather Owens, were in her car when the water overwhelmed them. She managed to escape but he did not; his body was found about 8:30 a.m. the next morning on the banks of the Patapsco River.

The large-scale damage on Main Street that the flood left in its wake was immediately apparent: cars belonging to patrons of restaurants like Tersiguel’s piled in the Patapsco River, debris lines that reached past the first story of some buildings and large chunks of sidewalk and building foundations eroded away.

Unique Problems

Steep slopes surrounding the historic downtown area that saw the most severe damage, adding a unique and recognizable landscape but also creating challenges during big storms.

Ed Lilley grew up in Ellicott City and has worked on Main Street most of his career. He is a longtime community organizer, sits on the board for the Ellicott City Partnership’s Clean Green and Safe Committee, works at the B&O Museum and was out on Main Street at 6 a.m. the morning after the flood signing up volunteers and taking donations.

“The unfortunate thing for Ellicott City is we are the bottom of the bowl,” he said.

The historic nature of a city founded in 1772 means that some of the development—and therefore impervious surface like roads, sidewalks and buildings—was built before managing stormwater runoff was considered a necessity. Impervious surfaces mean less water can be absorbed into the ground, and as water collects and moves more rapidly runoff becomes more hazardous.

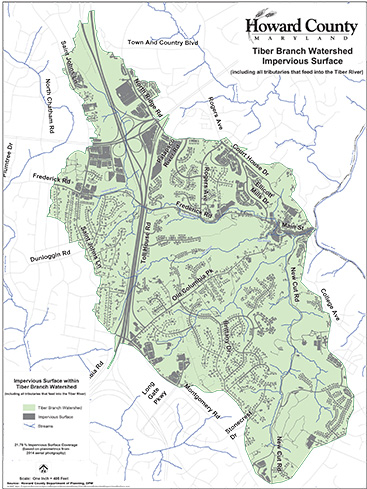

The Tiber-Hudson watershed, which includes Ellicott City, is about 21 percent covered by impervious surfaces. According to Cecilia Lane, stormwater coordinator for the Chesapeake Stormwater Network, “Any more than 10 percent impervious cover in the watershed and you will begin to see impacts.”

“We know that the storm and rainfall was exceptional, and that perhaps the best of systems could not have contained all of the runoff,” said Mary Catherine Cochran, executive director of the Patapsco Heritage Greenway. “But we don’t have the best of systems in place.”

Older developments and private property often have no way to manage stormwater runoff, Cochran explained. And although new developments have some stormwater mitigation in place, it may not be enough. “Even the newest developments have systems in place to handle 100-year floods, but not 1,000-year floods,” said Cochran.

The probability for a storm to bring such a large amount of rain in any given year was 1 in 1000 making it what experts call a 1,000-year storm. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean an event like July 30 will only happen every thousand years—in fact growing evidence shows that potentially flood producing downpours are happening more often.

Downstream

Downstream from Ellicott City, staff at the Patapsco Valley State Park are focused on flood recovery.

Maintenance coordinator Dennis Cutcher has seen the river go through many changes since he first began playing and fishing in it as a child in the 1960s and 1970s. He’s noticed more frequent flooding as more people have moved in and built homes around the river and its tributaries.

“I would say I’m close to it because of the simple fact that I grew up in that river,” Cutcher said. “I played in there since I was a little kid. It’s sort of a part of me if you want to look at it that way.”

More than a month after the storm, evidence of a flood still lingered: stray recycling bins, car tires embedded in newly-formed sediment islands, log jams piled high with uprooted trees that once stood 30 to 40 feet tall. Their intricate root systems seemed to grasp wildly in the wrong direction.

“When we get those heavy rains like we had, the river changes from one side to another,” Cutcher said. Sediment gets moved around shifting the flow of the river, vegetation gets washed away thereby destabilizing the banks and new beaches and islands form, which disrupts fish and other wildlife.

With the slightly above average rainfall that occurred in September, some of the logjams along the Patapsco have broken up, and the debris, including plastics and other trash, is headed downstream towards the Chesapeake Bay.

“As far as how debris affects the Bay, we know that the most persistent debris that will linger is plastic, since it doesn't fully break up,” said Julie Lawson, founder and director of Trash Free Maryland. “It may cause visual blight, but it also can absorb chemicals from the water and be ingested by aquatic life, both obviously negative environmental effects.”

Less visible but still concerning: a sewage overflow released more than 17 million gallons of untreated wastewater over about three days at Sucker Branch, a tributary to the Patapsco.

Adaptation is Key

With Ellicott City’s placement directly over a stream and very near a river, floods have been occurring for a long time. The scientific consensus is that they will continue—and, as climate change continues its trajectory, occur with greater frequency.

Future climate projections look at two scenarios: one in which emissions like carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere are significantly lowered, and one that assumes a continued increase in emissions. In the scenario where emissions are reduced, extreme daily precipitation events would occur twice as often from 2081 to 2100 as compared to 1981 to 2000. But if emissions continue to increase, those events would occur up to five times as often.

Local groups and government organizations have been and are working to mitigate the impact of severe flooding. Tom Schueler, founder of the Chesapeake Stormwater Network based in Ellicott City, says adaptation to more frequent flood producing storms and a careful examination of the science behind the flood should be the focus moving forward. Also the county has put in place Clean Water Howard that incentivizes commercial and private property owners to treat or remove impervious surfaces on their land by providing reimbursements for stormwater projects and a reduction in their watershed protection fee.

Without preemptive efforts by Restoring the Environment and Developing Youth or READY, the flood may have been even worse. They employ young people throughout Howard County who work in Ellicott City to maintain stream channels from Route 29 down to the Patapsco River.

The sense of community responsibility and the instinct to rebuild no matter what is apparent in Ellicott City. As of October 20, 2016, forty-four businesses have reopened, including Tersiguel’s French Country Restaurant, and another twenty-three have preliminary time frames for when they plan to reopen according to Howard County Executive Allan Kittleman’s Facebook page.

“No one fights as hard as these business people, and no one enjoys the town as much as those that live here. We have come back from floods, from fire and more floods,” Angie Tersiguel said as she and her husband Michel get their restaurant back up and running again. “We are still here. Striving and working to be the best we can be.”

To view more photos, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program's Flickr page

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories