Stormwater Runoff

When precipitation falls on roads, streets, rooftops and sidewalks, it can push harmful pollutants like fertilizer, pet waste, chemical contaminants and litter into the nearest waterway.

Overview

What happens to a drop of rain when it falls onto the ground? It may land on a tree and evaporate; it may land on a farm field and soak into the soil; or it may land on a rooftop, driveway or road and travel down the street into a storm drain or stream. Precipitation in an urban or suburban area that does not evaporate or soak into the ground but instead runs across the land and into the nearest waterway is considered stormwater runoff. Increased development across the watershed has made stormwater runoff (also called polluted runoff) the fastest growing source of pollution to the Chesapeake Bay.

How does stormwater runoff affect the Chesapeake Bay?

As stormwater flows across streets, sidewalks, lawns and golf courses, it can pick up harmful pollutants and push them into storm drains, rivers and streams. These pollutants can include lawn and garden fertilizers, pet waste, sand and sediment, chemical contaminants and litter.

Stormwater runoff can cause a number of environmental problems:

- Fast-moving stormwater runoff can erode stream banks, damaging hundreds of miles of aquatic habitat.

- Stormwater runoff can push excess nutrients from fertilizers, pet waste and other sources into rivers and streams. Nutrients can fuel the growth of algae blooms that create low-oxygen dead zones that suffocate marine life.

- Stormwater runoff can push excess sediment into rivers and streams. Sediment can block sunlight from reaching underwater grasses and suffocate shellfish.

- Stormwater runoff can push pesticides, leaking fuel or motor oil and other chemical contaminants into rivers and streams. Chemical contaminants can harm the health of humans and wildlife.

Stormwater runoff can also lead to flooding in urban and suburban areas.

Forests, wetlands and other vegetated areas can trap water and pollutants, slowing the flow of stormwater runoff. But when urban and suburban development increases, builders often remove these natural buffers to make room for the impervious surfaces that encourage stormwater to flow freely into local waterways.

Litter from stormwater runoff

Litter such as plastic bags, cigarette butts and beverage bottles eventually get carried by stormwater into sewer systems or waterways. Litter detracts from an area’s beauty, smothers aquatic plants and bottom-dwelling organisms, adds toxic contaminants to the water and makes animals sick. While nine in ten watershed residents never toss food wrappers, cups or cigarette butts onto the ground, about five percent of watershed residents sometimes, usually or always do.

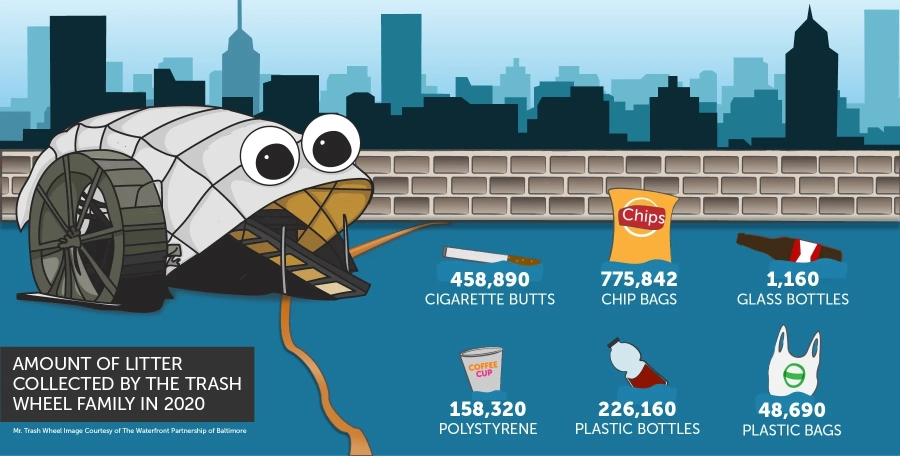

Show image description

Mr. Trash Wheel, a machine with large eyes, wheels and a chute, before a city skyline. Litter collection figures for 2020 appear: 458,890 cigarette butts; 775,842 chip bags; 1,160 glass bottles; 158,320 polystyrene; 226,160 plastic bottles; 48,690 plastic bags.

Watershed organizations around the region rely on volunteers to remove litter from waterways, and many cities have installed trash traps to capture litter and debris. In Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, a family of three water wheels nicknamed "Mr. Trash Wheel", "Professor Trash Wheel" and "Captain Trash Wheel" collected 1,608 tons of trash between May 2014 and January of 2021. In 2021, the city’s trash-collecting water wheel family will welcome it's fourth member: "Gwynnda the Good Wheel of the West". Gwynnda the Good Wheel is capable of collecting about 300 tons of trash and debris per year from the Gwynns Falls — more than the other three wheels combined.

What are impervious surfaces and why are they a problem?

Impervious surfaces are paved or hardened surfaces that do not allow water to pass through. Roads, rooftops, sidewalks, pools, patios and parking lots are all impervious surfaces.

Impervious surfaces can cause a number of environmental problems:

Impervious surfaces can increase the amount and speed of stormwater runoff, which can alter natural stream flow and pollute aquatic habitats.

Impervious surfaces limit the amount of precipitation that is able to soak into the soil and replenish groundwater supplies, which are an important source of drinking water in some communities.

Impervious surfaces that replace soil and plants remove the environment’s natural ability to absorb and break down airborne pollutants.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the presence of roads, rooftops and other impervious surfaces in urban areas means a typical city block generates more than five times more runoff than a forested area of the same size.

Impervious surface data are used to measure the rate of development across the watershed and to identify high-growth areas and patterns of sprawling development. Between 1990 and 2007, impervious surfaces associated with growth in single-family homes are estimated to have increased about 34 percent, while the region’s population increased by 18 percent. This indicates that our personal footprint on the landscape is growing.

How much pollution does stormwater runoff send into the Chesapeake Bay?

Stormwater runoff is the fastest growing source of pollution to the Chesapeake Bay. According to data from the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Watershed Model, stormwater currently contributes 17% of nitrogen loads, 17 percent of phosphorus loads and 9% percent of sediment loads to the Chesapeake Bay.

What you can do

To lessen the impacts of stormwater runoff on the Bay, consider reducing the amount of precipitation that can run off of your property. Install a green roof, rain garden or rain barrel to capture and absorb rainfall; use porous surfaces like gravel or pavers in place of asphalt or concrete; and redirect home downspouts onto grass or gravel rather than paved driveways or sidewalks.