By the Numbers: 877,000

In 2001, the Chesapeake Bay Program partnership designed a four-part learning experience to get students outside and instill in them a long-lasting environmental ethic. Seventeen years later, the partnership has released its second estimate of the number of students receiving this inquiry-based approach toward education, which is a crucial step toward determining where targeted resources could boost the adoption of a practice that can benefit student achievement and environmental health.

This approach toward education is known as the Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience, or MWEE (“mee-wee”) for short. What began as a method of advancing environmental literacy in the Chesapeake Bay watershed now supports science, social studies and other instruction in California, Hawaii, the Great Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, New England and the Pacific Northwest. In fact, a federal program managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and established to promote MWEEs through competitive grants has, since 2002, awarded more than $75 million to more than 670 projects in these regions.

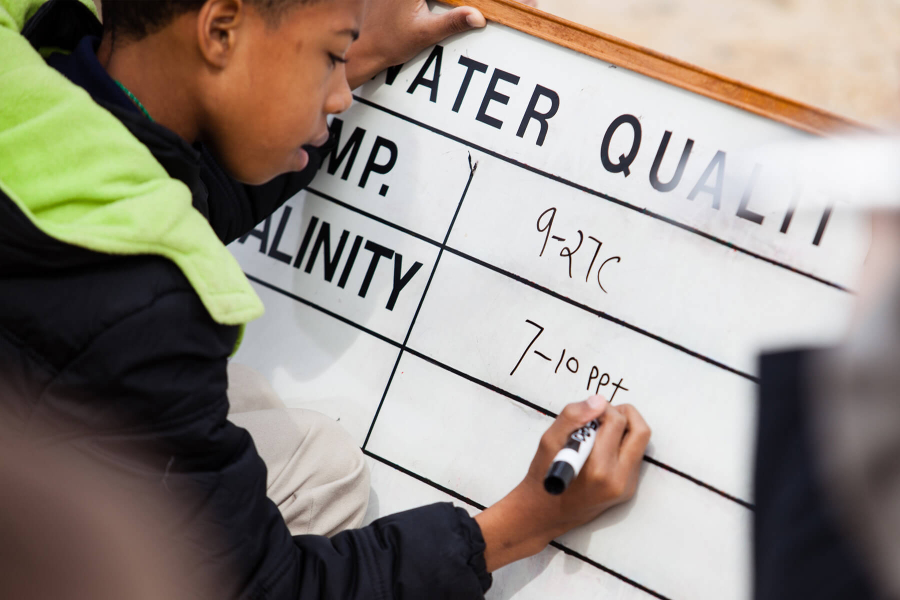

By asking students to investigate an environmental issue, collect data and information, and draw their own conclusions about the issue at hand, MWEEs create active learners, critical thinkers and effective communicators. By asking students to take action to address the issues they have explored, MWEEs foster a sense of environmental stewardship that will prepare them for a lifetime of community involvement and civic engagement. In other words, MWEEs make sure future residents of the region are prepared to pick up the mantle of the Chesapeake Bay Program’s work.

This is one reason expanding student participation in MWEEs is such an important pursuit of the partnership. “We’re trying to make sure that every single student growing up in the watershed is learning to ask questions about environmental problems, think through data and reach their own personal conclusions,” said Shannon Sprague, chair of the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Education Workgroup.

“When you process data and information and think through an issue, it more often than not leads you to a place of understanding and of stewardship,” Shannon said. “You have to have people who want to care for and be stewards of their environment if you want to have any hope of the long-term success of this [environmental protection and restoration] effort.”

By committing to the Environmental Literacy goal of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the District of Columbia committed to elevating environmental literacy. Their goal to provide every student in the watershed with at least one MWEE in elementary, middle and high school has motivated state and local leaders to advocate for this educational approach. But motivation to make MWEEs more mainstream is also coming from educators themselves.

“The education field is rallying around this idea of engaging kids in hands-on learning and teaching kids how to think rather than what to think. The MWEE lines up perfectly with this,” Sprague said. “It allows [educators] to meet their curriculum requirements in an engaging, thoughtful way that makes students want to come to school and want to learn.”

Last year, the Chesapeake Bay Program measured the extent of MWEEs across hundreds of school districts in the watershed. The resulting data revealed that 877,000 of the region’s 2.7 million public school students are enrolled in a district that provides MWEEs to at least one full grade or in one required course.

“We’re seeing awesome progress in Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C.,” said Sprague. “Most people are doing something, and a lot of people are doing everything.”

The gaps this survey data uncovered will help the Chesapeake Bay Program and its partners better target their work. In some cases, the data show where school districts could turn existing outdoor field experiences into full-fledged MWEEs. In others, it shows where school districts may need additional support to establish MWEEs for the first time. And in others, it shows where the sharing of case studies could build more MWEE momentum.

Because the Chesapeake Bay Program works across the entire watershed, it can convene state departments of education to discuss environmental literacy efforts and share lessons learned. The partnership is also working to provide individuals with the technical assistance that will turn them into “MWEE Ambassadors.” To that end, the partnership’s Education Workgroup released An Educator’s Guide to the Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience last year.

This manual includes tips for designing, implementing and gaining funding for a MWEE, as well as planning documents and other tactical tools. The Education Workgroup will create a series of training videos to complement this online guide this year.

“We want teachers to be able to build MWEEs at the classroom level,” Sprague said. “Yes, we hope districts will put in systemic MWEEs over time, but that doesn’t mean individual teachers can’t be doing this on their own. Because it’s a very interesting way to learn.”

Learn more about our work to increase student participation in MWEEs across the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories