Trees for All

Two day conference focuses on ensuring everyone has access to healthy tree canopies

Living things require few basics to survive – food, water, air to breathe. To really live, to thrive, living things need nourishment, sunlight and quality conditions. Living only on basics, a plant will grow steadily on, putting effort into survival and the production of leaves, but it may never burst gloriously into bloom. The same is true of people, and the two were brought together in the recent Chesapeake Regional Environmental Justice Workshop, Trees for All.

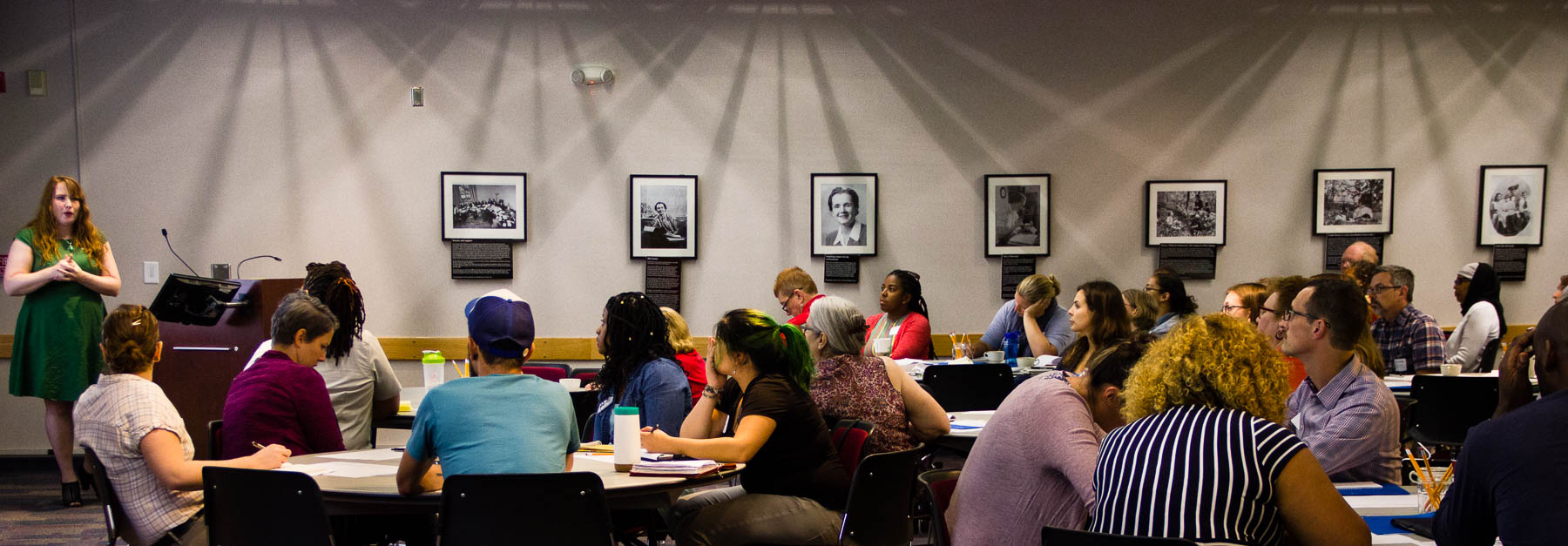

The workshop was held August 8-9, 2017 at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland with a diverse set of attendees from across the United States, who came together to learn from their peers about retaining and increasing a healthy tree canopy in their communities. Lillie Leaf Solutions CEO Sarah Anderson, who works to address equity, inclusion and justice in the environmental world, opened the conference with a message about being more effective in urban forestry by seeing the larger picture.

Advances in environmental sciences, like improved geographic information system (GIS) mapping, allow environmental professionals to pinpoint more precisely where directed efforts will have the largest impact on environmental health and restoration. The new maps show tree cover, streams, properties and cities in detail, revealing in the data the close geographic overlap of environmentally disadvantaged areas – particularly those lacking tree canopy – with socially and economically disadvantaged communities. Addressing tree canopy through the lens of environmental justice, or environmental justice as it relates to community trees, is a partnership which leads to a healthy overall system and teaches a valuable lesson about health and wellbeing for all life.

Trees provide shade, improve air quality and positively impact stream health, contributing to an increase in revenue from fishing industries, tourism and recreation, and leading to a rise in property values. Swaths of trees bordering streams – forest buffers – prevent pollution by cooling the water and keeping animals from wandering in and out of streams, contaminating the water. Areas that already have tree cover provide a natural barrier to the placement of industrial facilities, an issue which disproportionately impacts and creates disadvantaged communities. Dexter Locke, an urban ecologist with the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, summed up the interaction best with the striking statement, “Where trees are planted today and the amount of maintenance devoted to them affects where environmental justice issues are in the future.”

The two day conference was broken into panels and exercises. At the panels, experts delved into case studies and held dynamic question and answer sessions with the audience. Exercises were conducted in a meeting room broken into small round tables, where attendees worked together to overcome barriers of every origin and frame their various careers and projects in context. “[Trees for All is] a good conference for me to see the equity and inclusion piece and how that can fit into the WIP,” said Aaron Waters, environmental protection specialist with the District of Columbia Department of Energy & Environment (DOEE) in the audience. The “WIP” is the Watershed Implementation Plan, a guide that each Chesapeake Bay watershed jurisdiction creates to help meet their goals for reducing pollution while taking into account the continued economic improvement and quality of life in their communities.

Trees certainly do contribute to the economic health and overall situation for a city. Gloria Alejandra Antia, a park naturalist for the City of Miami Parks and Recreation Department, explained Miami’s new innovative plan to use trees to combat the collective issue of urban heat. “Our biggest drivers are tourism and agriculture,” explains Antia, “and they are weather dependent.” Urban heat, or the creation of heat islands, is of major concern. Heat islands are created in highly urbanized areas, where an abundance of paved surfaces can cause air temperatures to be as much as 22 degrees warmer than less developed neighboring areas.

Urban heat can cause double-digit increases in energy consumption for the city, leading to more emissions in the air from the power plants. Hotter pavement temperatures increase the temperature of stormwater after a rain. Poor air and impaired water exacerbate health concerns in an already overheated population, increasing discomfort and elevating tensions. Economic and social factors collide in a heat island, to the detriment of that city.

A complex problem like a heat island needs a complex answer, and the complexity of trees may just be that solution.

Effective tree management must begin on the premise that trees are not static beings. This understanding is reshaping how environmentalists address trees and the communities in which they grow, explained Don Vanhassent, director and state forester with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “Urban forestry is at least as much about dealing with people as it is about trees,” he addressed the crowd. The problem of “parachuting” organizations – those that drop into a community for a single project and then leave – has long damaged community relationships. A lack of planning for adult trees – which can foul power lines or become hazards when not maintained – can do the same. Several organizations are now working to remedy these issues by combining long-term planning with a more comprehensive approach.

New Jersey’s Green Streets reentry program does tree maintenance work, providing careers and a positive green job pathway for residents while ensuring that successful tree plantings remain assets to their communities. Orchard Baltimore is a group that plants fruit trees and organizes harvest parties for older fruit trees within communities. Harvest parties address existing problems by preventing fruit from rotting, creating an event for the community to come together and providing food as the harvest is distributed to the neighborhood.

The conference itself held to its values of addressing a larger picture: all leftover food – provided by the environmentally conscious caterer Green Plate – was donated to the food group Shepherd’s Table. Trees for All was supported through a grant from the USDA Forest Service in partnership with Chesapeake Bay Program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Prince George’s County, DC Urban Forestry Administration and the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. Whether in putting on a conference, caring for the environment or caring for people, partnership is key. Said one member of the audience during one of the question and answer sessions, “the best way to overcome a barrier is to share ownership.” For more information about the conference and what you can do to further efforts, please visit Lillie Leaf Solutions or the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Diversity Workgroup.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories