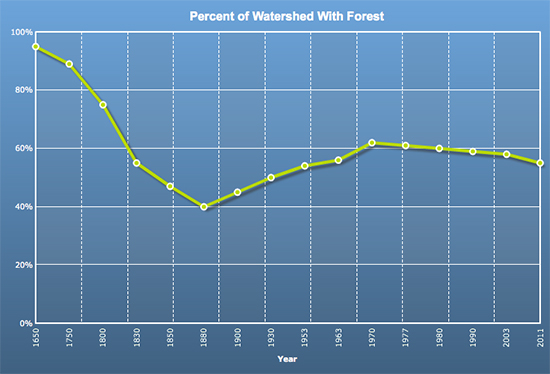

By the Numbers: 60

The percentage of Chesapeake forests that have been fragmented by development.

Three centuries ago, the Chesapeake Bay watershed was covered with trees. Maples, pines and oaks captured rainfall, stabilized the soil and offered food, shelter and migration paths to wildlife. But as the country was settled and developed, more people moved into the region, and forests were cleared for farms and communities and trees were cut for timber and fuel. The population of the region now stands at almost 18 million—more than double what it was in the 1950s. While valuable forests do remain in the region, many suffer from fragmentation: separation into smaller pieces that are vulnerable to threats.

According to a report from the U.S. Forest Service, 60 percent of Chesapeake forests have been divided into disconnected fragments by roads, homes and other gaps that are too wide or dangerous for wildlife to cross. The isolated communities of plants and animals that result have smaller gene pools that make them more susceptible to disease. The sensitive species that thrive in the moderate temperatures and light levels of an “interior” forest (which is mature and separate from other land uses) can’t find the unique habitat characteristics they need. And the forests themselves are more vulnerable to invasive species and other threats.

In an effort to reconnect fragmented forests, conservationists have turned to wildlife corridors. These corridors give wildlife the space to move and can be found around the world. The World Wildlife Federation runs the Freedom to Roam initiative to protect corridors along the Northern Great Plains and Eastern Himalayas. The National Wildlife Federation runs the Critical Paths Project to cut the number of fatal road crossings for animals in Vermont. And watershed states like Maryland and Virginia have incorporated wildlife corridors into their green infrastructure plans.

Even local landowners have contributed to the corridor movement: in September, the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay recognized Christine and Fred Andreae as Exemplary Forest Stewards for their work to manage 800 acres of forestland—including a corridor that connects George Washington National Forest and Shenandoah National Park—along the Page and Warren county lines in Virginia.

Christine and Fred placed the property under conservation easement through the Virginia Outdoors Foundation, which was established by the Commonwealth in 1966. The Andreaes have also convinced their neighbors to follow suit: what started as an agreement between Christine, Fred and one neighbor to connect a patch of land on two sides of the Shenandoah River eventually expanded to include eight property owners and 1,750 contiguous acres. Today, bald eagles and bears abound on the land that can be seen from Skyline Drive.

“[Our neighbors] wanted to keep the land undeveloped,” Fred said when asked how he motivated others to join the conservation cause. “Most of them had family connections to the land—some [spanning] 100 years or more. It was their heritage they wanted to see preserved.”

The Andreaes have made their property as self-sustaining as possible so that once their two sons inherit it, it won’t have to be sold. “We’ve done something that will last. That’s a legacy. That will be there, theoretically, forever,” Fred said. “There aren’t too many things you can do that will be there after you’re gone—that will have an impact on my family and the other people who live in the area.”

Through the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, the Chesapeake Bay Program has committed to expanding urban tree canopy and restoring hundreds of thousands of miles of streamside trees and shrubs. Learn more about forests and our work to protect them.

Comments

Nicely written piece. Thanks for it.

Side note: I'd not previously seen the graph of long-term history of forested land fraction. Although I suspect versions of it are out and about, yours is clear and well done. (Thanks for anchoring the y-axis at 0%!) I knew forested land had rebounded for a while (with agricultural decline) but was unaware that its renewed decline dates back to 1970. A geographical breakdown of this by region would be enlightening.

One minor complaint: It would be nice to know the source of the data for this graph (e.g. parenthetical info in its caption.....)

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories