10 reasons to be hopeful about the Chesapeake Bay in 2024

Rebounding oysters, shrinking dead zones and unprecedented funding gives us hope

Protecting the 64,000 square miles of land and water within the Chesapeake Bay watershed is an immense challenge. But if you look across the region, you will find many reasons to be optimistic. Rivers are rebounding, key species are recovering and the resources, partnerships and science needed for impactful restoration are only getting stronger.

Here are 10 reasons to be hopeful about the Chesapeake Bay in 2024.

The dead zone was the smallest it’s ever been in 2023

In 2023, the Chesapeake Bay dead zone was the smallest it’s been since 1985, when Maryland and Virginia first started measuring. Dead zones are areas of little to no oxygen that form when nutrient pollution runs off into the water and causes algae blooms, which suck oxygen out of the water after decomposing. Blue crabs, oysters and other wildlife cannot survive in dead zones and those areas become off-limits to commercial seafood harvesters.

Oyster populations are coming back

A fall 2023 survey showed that oysters were reproducing at a rate that was nearly four times higher than the 39-year median. In the same survey, juvenile oysters were found in parts of the Bay they’ve rarely been found. This follows the record-breaking amount of oysters that were harvested in both Maryland and Virginia in 2022 and 2023. Going into 2024, the Chesapeake Bay Program has restored oyster habitat in eight tributaries of the Bay and is expected to complete work in three more rivers by 2025.

Protected lands in the watershed increased from 19% to 22%

As of 2023, 22% of the lands within the Chesapeake Bay watershed are permanently protected from development. Whether it’s a farm, forest, wetland or park, these natural spaces are critical for maintaining clean rivers and streams and providing habitat for wildlife. The partnership is committed to protecting 30% of the land in the watershed by 2030, aligning with the White House’s goal of conserving at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030.

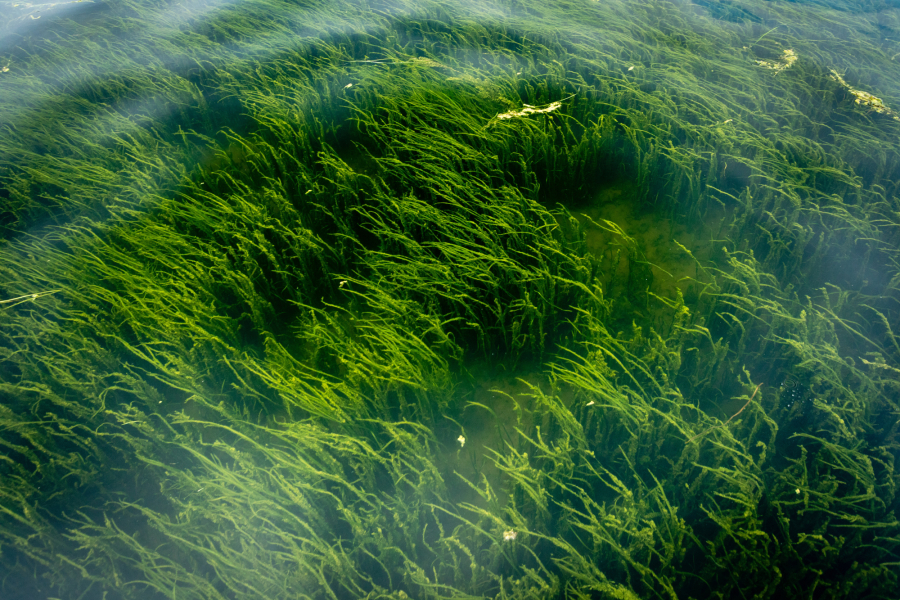

Underwater grass is rebounding in places across the watershed

While the total amount of underwater grasses in the Bay is below the 2025 restoration target of 130,000 acres, there are many parts of the estuary where grasses are thriving. The resurgence of underwater grasses in the Susquehanna Flats has been occurring over the past several years, and in 2022, the area gained another couple hundred acres. Both Maryland and Virginia’s portion of the Tangier Sound—a hotspot for blue crab harvesting—gained thousands of acres, increasing by 54%. Mobjack Bay and the Pocomoke River are two other areas where grasses increased significantly in 2022.

Major Chesapeake Bay tributaries are improving

Water quality monitoring data collected by the Chesapeake Bay Program shows that several major tributaries of the Bay are seeing less pollution. Throughout much of the Patuxent and Potomac rivers in Maryland, we are seeing a long-term trend (1985-2022) of decreasing nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. At monitoring stations through the James River in Virginia we are also seeing improving trends for nitrogen and phosphorus over that same time period. In the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., monitoring shows that water clarity is improving over the long term (30 years) and chlorophyll-a is improving over the short term (10 years). These measurements indicate that the rivers are getting cleaner which means improved habitat for wildlife and safer conditions for recreation.

We have historic funding for Bay restoration

Funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has provided an unprecedented level of funding to the Environmental Protection Agency, which is being distributed to organizations across the watershed. The funding is being used to plant trees, restore wetlands, upgrade wastewater treatment plants, increase research and much more. These efforts will have a lasting impact on the watershed, particularly in communities adversely affected by environmental hazards such as polluted water and extreme heat and flooding.

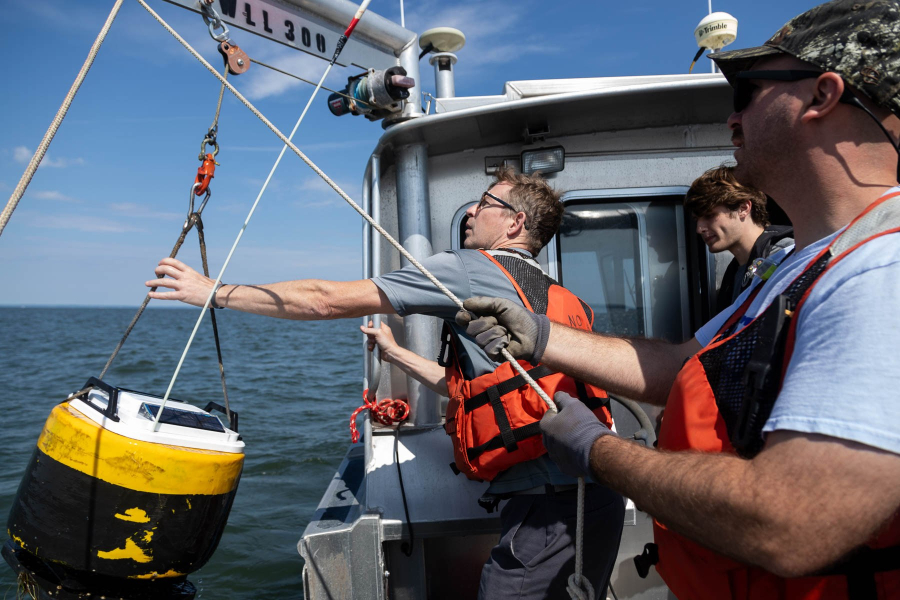

We know more about the Bay than ever before

The Chesapeake Bay Program has a variety of new scientific tools and resources heading into 2024 that will help guide clean water efforts across the region. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will be deploying 10 monitoring stations between 2023 and 2025 that will provide 24-hour, real-time readings of oxygen levels in the water. The Chesapeake Bay Program’s Rising Watershed and Bay Water Temperatures report has identified the best strategies for moderating the temperature of rivers and streams, which have increased due to climate change and land use practices. Additionally, the partnership has developed a roadmap for meeting the goals and outcomes of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, many of which have a targeted deadline of 2025.

The streams in the Bay watershed are getting cleaner

Between 2012 and 2017, the partnership assessed and estimated the health of streams across the watershed, determining that 67% of stream miles are considered healthy. When data was first collected between 2000 and 2005, just 57% of stream miles were estimated to be healthy. The partnership is on track to reach 70% of healthy stream miles by 2025, the goal set in the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement.

Innovative programs are helping farmers reduce pollution

Nutrient and sediment runoff from farms is one of the biggest threats to the Bay, but new approaches to reducing pollution are paying off. With support from the EPA, the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay has formed three corporate sustainability partnerships in which the food companies buying dairy products or the stores selling those products are helping farmers fund pollution reducing practices, such as stream fencing, forest buffers and manure storage pits. In Pennsylvania, the state with the most agricultural pollution entering the Bay, the EPA is distributing $14 million to farmers to implement similar practices. We’re also seeing more effective outreach strategies, such as those in Salisbury Township where conservation groups visited every farmer in the area to accelerate the adoption of pollution reducing practices.

Communities across the watershed set ambitious tree planting goals

Jurisdictions across the Chesapeake Bay watershed are all striving to increase tree canopy in an effort to combat climate change, protect their waterways and promote tree equity. Maryland has a goal of planting five million trees by 2031, the Keystone 10 Million Trees Partnership is working to plant 10 million trees across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania by 2026, Delaware set a goal of planting a tree for every Delawarean, New York plans to plant 1.7 million acres of new forest by 2040 and Washington, D.C. is to striving to achieve 40% tree canopy cover by 2032. Over the past two years, the EPA has leveraged money from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, in addition to their regular appropriations, to fund $9.6 million in projects to increase tree plantings in both agricultural and urban landscapes. Additionally, the U.S. Forest Service will invest $164.6 million from the Inflation Reduction Act in coming years to support urban and community forest efforts across the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Success stories can be found across the entire Chesapeake Bay watershed. What stories are making you hopeful? Let us know in the comments!

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories