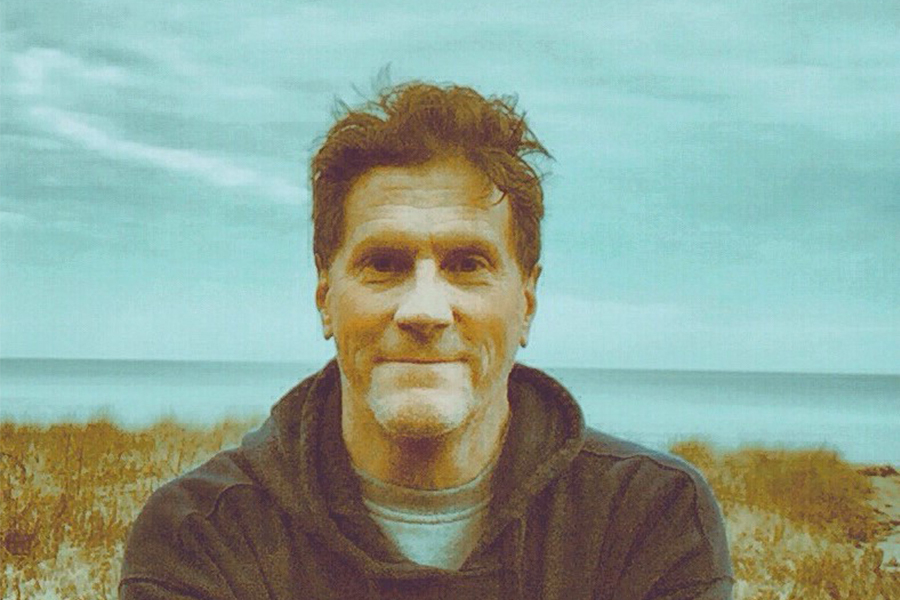

My Clean Water Story: John Wolf

Following a passion for both art and science in the environmental protection field

One of my earliest memories … of anything … was of a visit to an elderly neighbor’s house down the street one day. It is an odd memory because I was afraid of Old Lady Schwartz and didn’t want to end up in a Hansel and Gretel situation. After all, she appeared ancient to my four or five-year-old self—possibly as old as fifty!

Anyway, during the visit, she showed me a magical-looking device that turned out to be an antique stereoscope. Made almost entirely of wood, it included a goggle-shaped eyepiece to look through on one end and space for two images on the other end (imagine a 19th century version of modern virtual reality goggles). Having captured my attention, Mrs. Schwartz inserted two slightly different photographs that allowed me to see a picture of a landscape as a three-dimensional (3D) scene. At the time I thought it was very cool—enough so that I can still recall my amazement all these years later. Little did I know it would foreshadow my lifelong interest in 3D visualization.

In hindsight, I can see that my childhood interests often included science or art, and were strongest when the two were combined. My father was a chemist who spent his free time doing woodwork, while my mom was a schoolteacher who pursued a variety of textile arts, so there was always an appreciation for both disciplines in the household. In elementary school, art was one of my favorite classes. I recall enjoying the classic shoebox diorama project so much that it led to a mini hobby of manually fabricating “ecosystems” as 3D scenes. In fifth grade, after being offered extra credit to write a short story about being stranded on a desert island (perhaps associated with Robinson Crusoe or a similar novel), I spent my allotted time making a detailed map of the imaginary island instead of composing the story. So … no extra credit for me … but the seeds for a future interest in cartography had been planted.

By middle school, my interest in the environment started to form. In the sixth grade, a few classmates and I created our elementary school’s “Protect Your Environment” club. Our focus was on litter cleanups in and around public spaces in Frederick, Maryland. In hindsight, it was likely an inappropriate activity to have 11-year-olds in charge of picking up what could have been dangerous debris, yet not only did we survive but I ended up with a lifelong appreciation for the need to care for the natural world.

Fast forward a decade or so to my first real job after graduating from college. I was fortunate to be hired to process conservation easements for the Maryland Environmental Trust (MET) as a result of Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay Initiatives back in the 1980s. My efforts focused on the protection of Chesapeake Bay waterfront lands and the experience drove home the importance of landscape conservation as the most cost-effective approach to protecting water and other natural resources.

But it wasn’t until the end of my tenure with MET, four years into my career, that I discovered my true passion in the field of environmental protection.

It happened at a geographic information systems (GIS) conference in Towson, Maryland. The luncheon keynote speaker, renowned landscape architect Ian McHarg, gave a passionate hour-long presentation that demonstrated the use of “GIS technology” before GIS became computer-based. His presentation incorporated visuals in a way I’d never seen before, through map overlays that connected data across multiple scientific disciplines. Immediately after the talk, I was hooked—not only because I had been captivated by McHarg’s stage presence (chain smoking and peppering in profanities in a thick Scottish accent) but because his approach to ecological planning was multi-disciplinary and inherently visual.

Soon after, I made somewhat of a mid-career adjustment to focus on using GIS to achieve natural resource objectives, which ultimately brought me to the Chesapeake Bay Program.

Today, I serve as the GIS Team Lead for the Bay Program, developing GIS and other data visualization efforts that help the partnership achieve its conservation and restoration goals. During my time here I have completed a masters’ GIS program as well as a doctoral degree focusing on interactive 3D mapping and design for land conservation. In each of these academic endeavors, and increasingly in my regular job, my projects combined elements of ecology, geography, technology and design.

I’d like to say that it was all planned that way, but for me, my current role came about by being open to new opportunities and never forgetting my passions for science and art. That career path has been anything but linear, with stops along the way in local, state and federal government, and now in a less formal capacity in the local land trust community. Clean water is a common, although sometimes indirect, theme among all these experiences.

Or maybe, after a half-century, I’m still trying to make the perfect shoebox diorama.

Comments

Back in the 70s and early 80s, some universities were closing geography departments. Then came GPS and GIS! Good work, Dr. Wolf!

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories