Seven locations around the watershed that hold a connection to the Underground Railroad

The Chesapeake Bay watershed has born witness to several important, critical moments in history—but perhaps nowhere else in America did a region play such a significant role in the Underground Railroad, an informal network of routes, safehouses and resources used by enslaved African-Americans to journey to their freedom. While the watershed ultimately became a place for hope among enslaved people, we must also acknowledge its painful past. In 1619, the first enslaved Africans arrived at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, and most of the ports along the Bay were important to the slave trade.

In 1998, Congress passed the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Act to honor, preserve and promote the history of resistance to enslavement through the Underground Railroad. Every jurisdiction in the watershed (Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia) has a connection to this important period. Let’s take a short journey through some of these sites around the watershed.

First Baptist Church of Elmira (Elmira, New York)

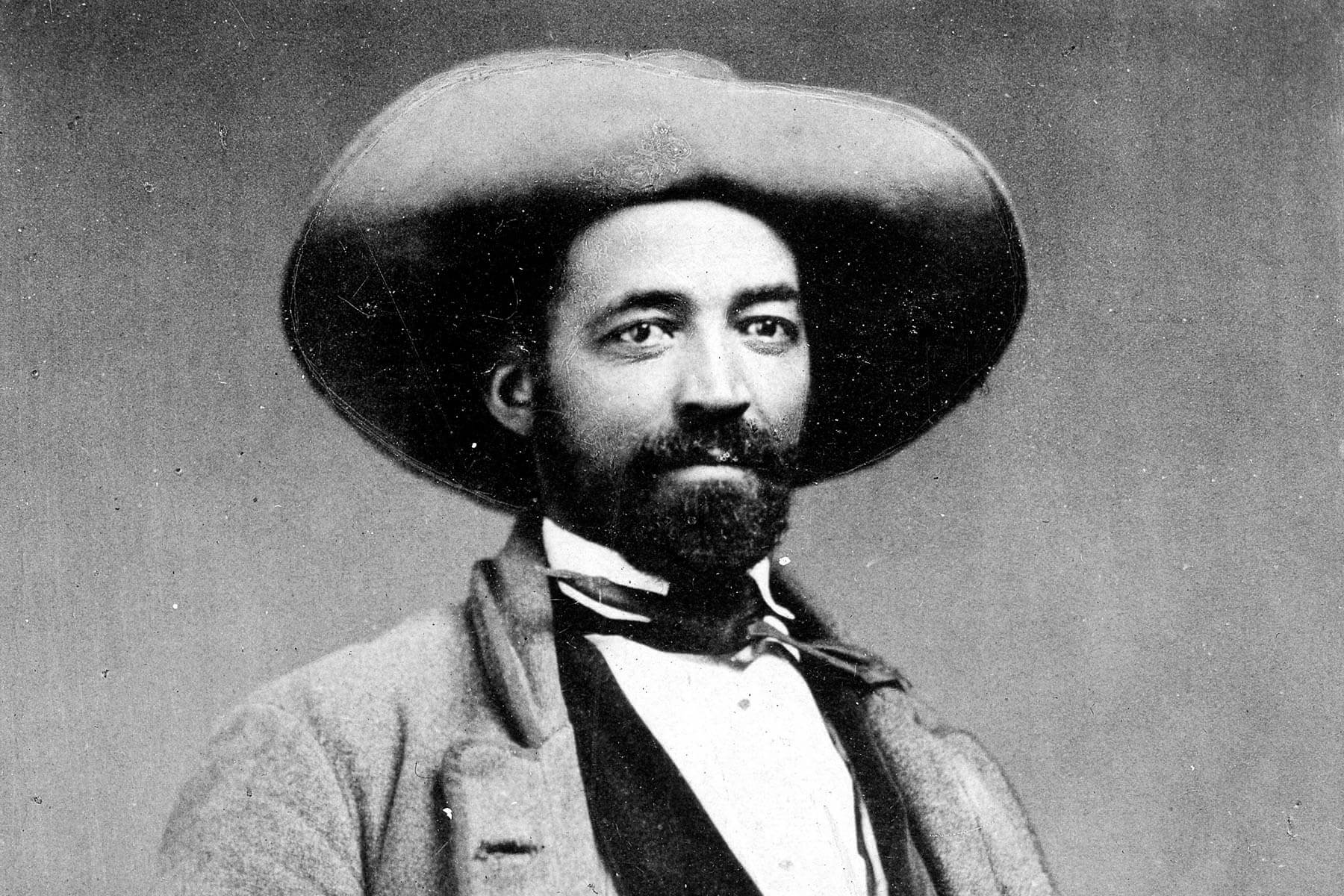

John W. Jones traversed the Underground Railroad himself to escape to freedom in Elmira, New York, where he eventually became sexton of the First Baptist Church. He eventually took command of the Underground Railroad in Elmira, where his church became a key station along the route. Jones also sheltered fugitives in his private home, ultimately helping over 800 people flee to Canada in search of freedom. He was assisted by several prominent townspeople, including William Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. While the First Baptist Church no longer stands, visitors can tour Jones’ home, which was located adjacent to the church.

Gateway Park and Riverwalk (Seaford, Delaware)

Harriet Tubman is one of, if not the, most famous inhabitant of the Delmarva region. It is estimated that she made 13 separate trips to Maryland to lead 70 people to freedom in her lifetime. It was on one of these trips that Tubman located an enslaved woman named Tilly, at the request of her fiancé. Tubman and Tilly traveled from Baltimore, Maryland to the town of Seaford, Delaware, where they hoped to catch a steamboat up the Nanticoke River. They landed at what is now known as Gateway Park, along Seaford’s Riverwalk. Historians consider this journey to be one of Tubman’s most complicated. Along the trip, she and Tilly were nearly arrested by slave hunters, acquired falsified papers stating they were free women and traveled an indirect route through the Eastern Shore to evade capture. This is the only documented escape in the headwaters of the Nanticoke. Visitors to the Riverwalk will find a plaque marking the spot where the women landed in Seaford.

Harpers Ferry (Harpers Ferry, West Virginia)

There is only one site known so far to have been associated with the Underground Railroad in the Chesapeake Bay watershed portion of West Virginia, but its notoriety is well known. While the area does have several documented escapes made by enslaved people, its connection to the Underground Railroad is most well-known through John Brown’s Raid. In 1859, Brown and a group of 21 men took over the armory, arsenal and rifle factory located in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, while taking two enslavers hostage and freeing the people they had enslaved. His raid was an attempt to start a revolt and ultimately destroy the institution of slavery. The U.S. Marines, led by Colonel Robert E. Lee, were eventually sent to the area to put down the insurrection, and Brown was captured and later executed after being found guilty of treason.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary House (Washington, D.C.)

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was one of the most well-known female abolitionists in the 19th century. Born a free Black woman in Wilmington, Delaware, Shadd Cary’s childhood home was used to hide enslaved people making their way north. After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, she emigrated to Canada where she founded the country’s first anti-slavery newsletter, The Provincial Freeman. She found success as lecturer and publicly raised money to assist those formerly enslaved that had run away. After the Civil War, she returned to the United States, settling in Washington, D.C., where she enrolled at Howard University Law School. She is recognized as one of the country’s first Black female attorneys and spent the rest of her life championing Black and female rights. While not open to the public, her former home can be seen at 1421 W Street NW.

William C. Goodridge House (York, Pennsylvania)

Freed when he was 16 years old, William C. Goodridge learned the trade of a barber, eventually opening up his own shop in York, Pennsylvania in 1827. Over time, he became a successful businessman, in part due to his “Oil of Celsus and Balm of Minerva,” a treatment for baldness that he created. As one of the most prominent Black Americans in southcentral Pennsylvania, Goodridge also opened his own railroad freight service running between York and Philadelphia. In addition to transporting goods, Goodridge used his rail service to transport enslaved people traveling along the Underground Railroad. At the William C. Goodridge House in York, his former residence, you can still see a secret hiding spot underneath his kitchen floor. He was involved in such notable rescues as helping Osborne Perry Anderson, the sole survivor of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, be smuggled into Philadelphia; and aiding William Parker and companions escape after the Christiana Riot.

Perryville Railroad Ferry and Station Site (Perryville, Maryland)

The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore (PW&B) Railroad Company ran through Perryville, Maryland, at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Dozens of enslaved people used the railroad during their journey north, many being hidden in boxcars fitted with secret compartments. One of the most famous to have come through this area was Frederick Douglass, who later recounted his journey. Borrowing papers from a friend, Douglass boarded a train in Baltimore. He recalled the moment when the conductor came to check tickets and papers as “one of the most anxious I ever experienced.” Another enslaved person who traveled on a train through Perrysville was Henry “Box” Brown, who lowered himself into a two-foot tall, three-feet deep wooden crate, and shipped himself from Richmond to Philadelphia—a journey taking 27 hours.

The Perrysville Station also plays a starring role in the kidnapping saga of Rachel Parker, a free Black woman working as a live-in servant in Pennsylvania, but near the state line. In 1851, she was kidnapped by slave hunters and taken to Baltimore, where they tried to pass her off as fugitive and collect a reward. Her kidnapper, Thomas McCreary, was known to have pulled off this scheme several times in the past, even kidnapping Parker’s younger sister, Elizabeth. However, while on the journey, two men at the Perrysville Station noticed she was in distress and followed her all the way to Baltimore. With assistance from a Baltimore Quaker, the two men were able to rescue Parker. Unfortunately, she had to wait a year before appearing before a judge; but had over 60 witnesses travel to Baltimore to attest she was free. Two of those witnesses included the sons of Thomas McCreary. The former site of the Perrysville Station is now located underneath the Perry Point VA Medical Center.

Tangier Island (Tangier Island, Virginia)

In 1814, Fort Albion was built by the British on Tangier Island. While its main purpose was to sustain continued attacks by the British during the War of 1812, it also ended up serving as a depot for receiving runaway enslaved people. During April 1814 to March 1815, nearly 1,000 fugitives arrived on Tangier, where they immediately became British citizens, as slavery was then illegal in the United Kingdom. The escapees were given the choice of becoming part of the British military or being sent to the British West Indies. Upon the British’s loss in the War of 1812, the fort was abandoned and burned to the ground in March 1815. At that time, any formerly enslaved people were sent to the British colonies in the Caribbean and Canada. The area where the fort once stood on Tangier Island has since eroded into the Bay.

Check out the National Park Service’s robust database of over 690 locations around the country that were important to the Underground Railroad or African-American history.

Comments

Thank you! This is a wonderful piece.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories