Living Classrooms Foundation brings Baltimore to life

Masonville Cove provides meaningful watershed educational experiences

Nestled squarely in the middle of a shipping terminal, a construction material company, a highway and the Patapsco River, the Masonville Cove Education Campus is a hidden gem in industrial southern Baltimore. Once the site of an illicit dump, Masonville Cove has been transformed into a place for residents to connect with nature thanks to almost a decade of restoration work funded by the Maryland Port Authority (MPA), a state agency whose goals are closely aligned with the stewardship of Maryland’s natural resources and well-being of neighboring communities.

Masonville Cove’s once-neglected waterfront is now home to more than 50 acres of conserved land, including wetlands, trails and a bird sanctuary. In the southwestern part of the property, the deceptively large “near zero, net energy” education center is powered in part by solar and geothermal energy. It contains a gathering room on its first floor, two classroom laboratories in the basement and a winding mural depicting the Port of Baltimore on the staircase between the two.

It’s a cool Wednesday morning in late March, and a bus full of students pulls up outside of the campus’ environmental center. These fourth-graders from Federal Hill Preparatory School are participating in the last day of the School Leadership in Urban Runoff Reduction Project (SLURRP) with Living Classrooms Foundation, which works to inspire young people through hands-on education and job training. SLURRP was originally funded by NOAA, whose grant program supports the Chesapeake Bay Program’s commitment to give every student in the region a meaningful watershed educational experience. Today’s trip was provided at no cost to the school, with support from MPA.

As part of SLURRP, Living Classrooms instructors have been visiting the students at Federal Hill one Friday a month for the past five month, teaching them about water quality issues, stormwater runoff, watersheds and much more, focusing on the Baltimore area. Today’s field trip to Masonville Cove is the capstone event of the fourth-graders’ SLURRP education.

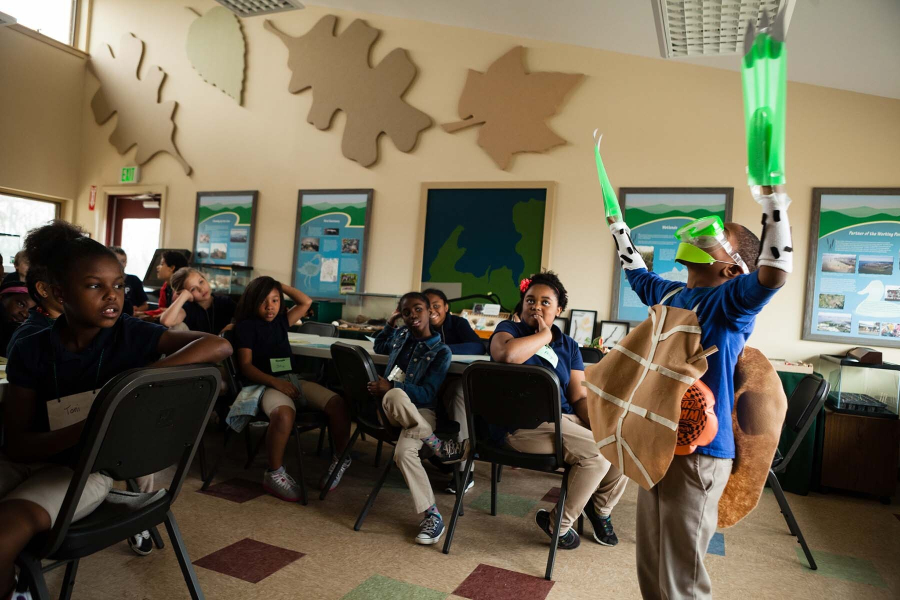

In the morning, the gathering room was full of fourth-graders, but they were quickly split into two groups for activities. One group went to the laboratories to play trash-sorting games while learning about plastics in waterways, and the other headed outside to collect water data on the Patapsco River.

It’s a cool day, but clear and comfortable—great for outside learning. As the water quality group heads over to the river, they cross over a stormwater outflow pipe, and Living Classrooms instructor Michelle Koehler stops the kids. “Every time [our staff] come[s] out to classrooms, we talk about runoff and runoff pollution,” she says. “It just so happens that in this neighborhood where Masonville Cove is, any storm drain empties out right here,” she explains, gesturing toward the water flowing out from under their feet.

Koehler continues walking with the kids towards the Patapsco, where they collect a bucket of water from the river and measure its temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen levels, trying out scientific testing kits and tools like refractometers.

In the afternoon, the kids again spent time both outside and inside. In the laboratory, students used microscopes to identify types of plankton in samples from the river. Outside, students used iPads to observe and document evidence of animals in the area, searching for signs such as prints, fur and feathers.

For the students, this field trip may mark the end of five months of learning about the Chesapeake Bay—but it’s far from the end of their learning about the watershed and the roles they play within it. Multiple students said that their favorite part of the day was testing water. “I like to see how the scientists work,” said Abigail Bayard, while another student, Alex Dixon, commented that he wants to go home and test the water in his house. After instructors brought out a diamondback terrapin for them to observe, Henry Lentz, watching calmly but intently, remarked, “I’ve never seen a turtle that close.” From turtles to tracks, Living Classrooms brought the Chesapeake Bay watershed to life.

To view more photos, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Flickr page.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories