What this summer’s rainfall could mean for the Bay

Record-high water flows test the Bay’s resilience

This summer has been a wet one for much of the Chesapeake Bay region. Pennsylvania saw its wettest July and August on record, and both Virginia and Maryland received much more rain than normal, with Maryland chalking up its second-wettest July. All of this led to the Bay receiving unusually high amounts of fresh water.

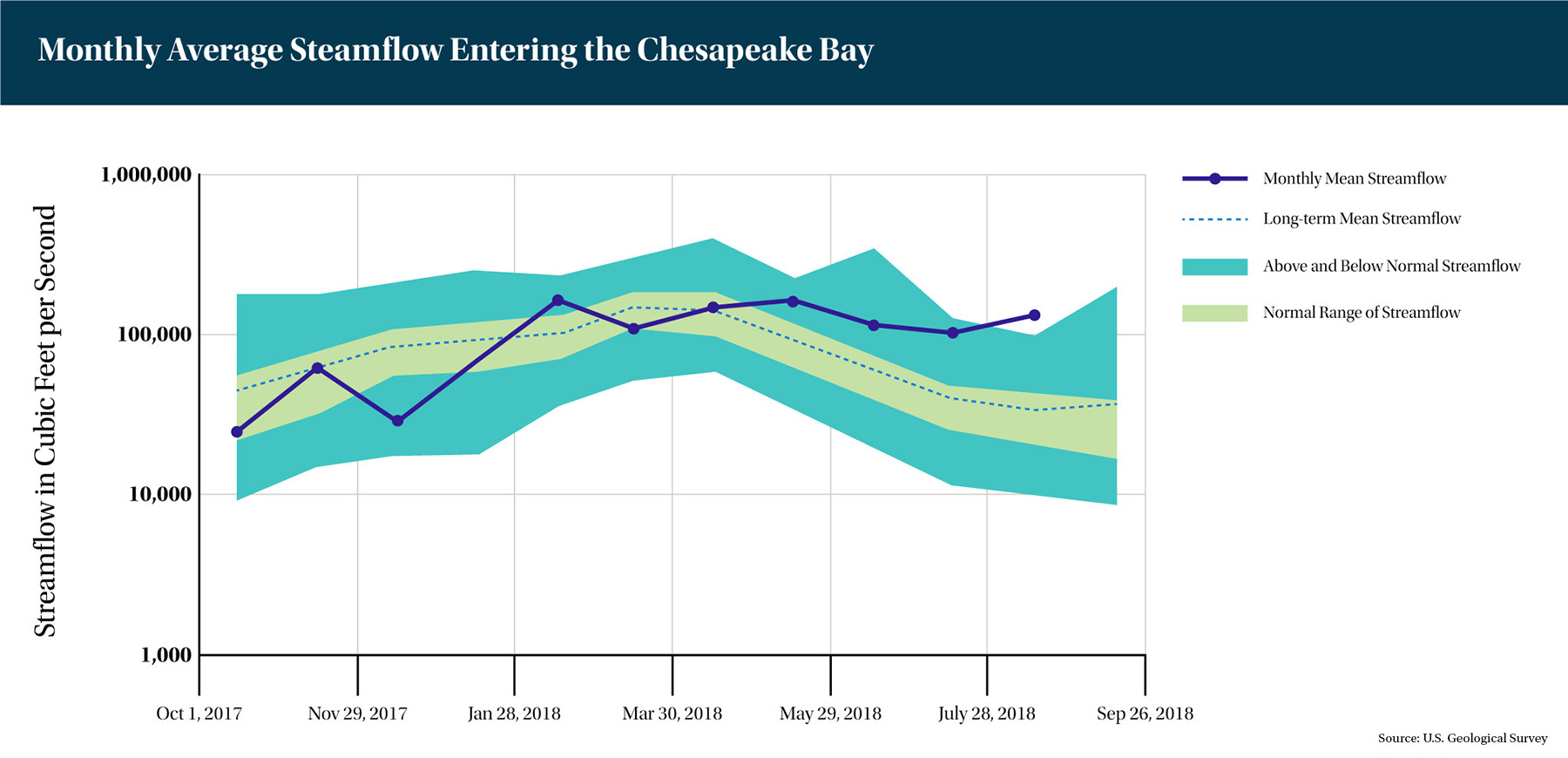

The Susquehanna River, which begins near Cooperstown, N.Y., flows through Pennsylvania and enters the Bay at Havre De Grace, Md., is the Bay’s largest tributary. Normally, it contributes about half of the Bay’s fresh water. This summer, the Susquehanna has reached record high flows, peaking in July at 375,000 cubic feet per second, the highest flow the river has seen since Tropical Storm Lee in 2011.

Because of the high amount of water flowing down the Susquehanna, Exelon, the operator of the Conowingo Dam which sits on the river, opened the dam’s floodgates multiple times. That’s unusual for summertime, since flows tend to be higher in the late spring and early fall.

Opening the dam released debris that had built up behind its walls, including everything from tree trunks and branches to plastic bags and water bottles. The volume of debris was the largest in 20 years, according to Exelon. In a statement, they noted that so far this summer, they removed 1,800 tons of trash from behind the dam, compared to the usual average of 600 tons.

The debris isn’t the only thing rushing out from behind the dam. During large storms and severe floods, sediment and attached nutrients are washed from the land and carried down the Susquehanna River, and into the Chesapeake Bay. The Conowingo Dam and reservoir used to hold large amounts of the sediment which kept it from reaching the Bay. However, the reservoir has reached its sediment storage capacity so more sediments and nutrients are delivered to the Bay during high flows.

The Susquehanna River basin wasn’t the only waterway to have a record-setting summer. During the week of September 17, the James and Potomac Rivers also saw high flows, thanks to the extend wet season plus the abundant rains from Hurricane Florence.

Because of this summer’s many storms, USGS estimates that rivers around the watershed contributed the highest monthly August flows, and second-highest July flows to the Bay on record. The flows during August were four times greater than the monthly average, according to Scott Phillips, the USGS Chesapeake Bay Coordinator.

While Florence won’t have nearly the impact here that it had on the Carolinas or southern Virginia, its rains have caused river flow to increase across the watershed.

Scientists had expected the potential effects of rainfall and runoff from Florence probably would be short-lived, but they are adding to the amounts of pollutants entering the Bay due to an unusual extended period of above normal river flow this year.

What does this mean for the Chesapeake Bay?

Too much rain and runoff can cause problems for the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay’s land-to-water ratio is 14 to one—the largest of any coastal water body in the world—meaning that all of the rain that falls onto its 64,000-square-mile watershed can have big consequences in the Bay. It will take time to measure and understand the impacts on the Bay, but here is what we can say so far.

The Bay is less salty.

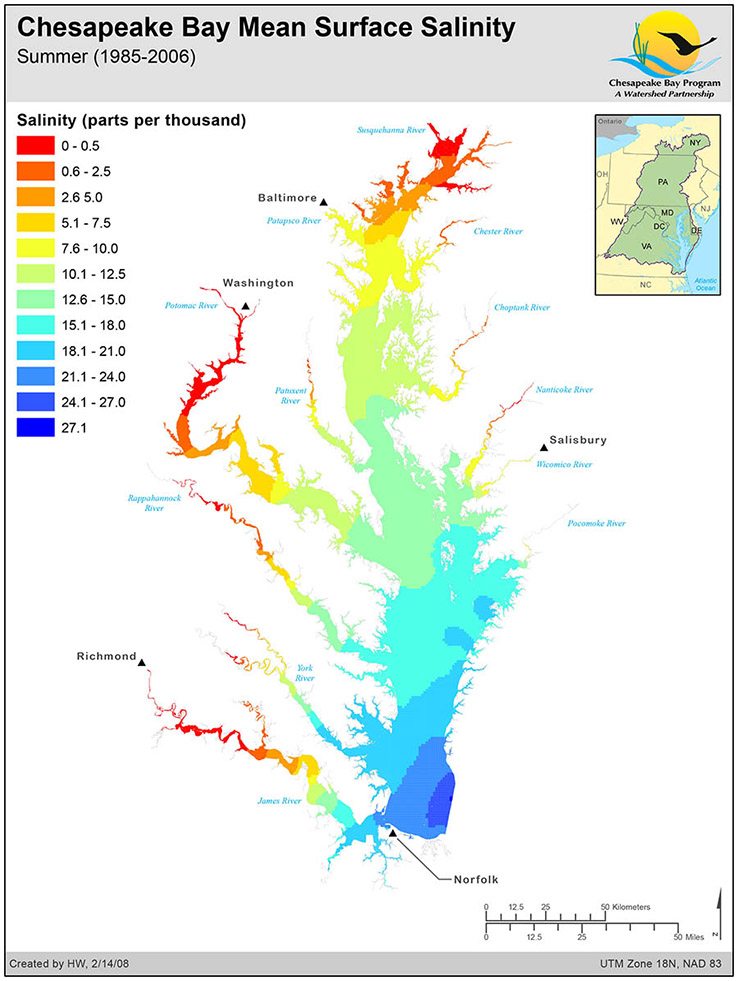

The Chesapeake Bay is an estuary: a body of water where fresh and salt water mix. Since the Bay receives fresh water from its rivers, mainly the Susquehanna in the north, and salt water from the Atlantic Ocean in the south, salinity levels vary by location. In general, Bay waters in the north are fresher and increase in salinity as you head south.

This year, we’ve seen record freshwater flows from the Susquehanna River and other major Bay tributaries such as the Potomac River, diluting the Bay and making it less salty. Waters in the south are still saltier, but the salinity gradient has been pushed down, and areas in the middle have less salt than usual.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has a series of buoys around the Bay that collect real-time water quality data, which have recorded this change in salinity. Bruce Michael, director of Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Resource Assessment Service, said DNR’s monitoring has shown the same results.

Changes in the location of fresh and saltier waters, in turn, could have wide-ranging impacts on the Bay’s plant and animal life.

Shellfish, particularly oysters, could be impaired.

Oysters require salty waters and they can’t move if conditions change. They can close their shells, but only for a short period before they begin to suffer. Also, extra sediment that arrives in the Bay with additional fresh water flows could smother reefs and suffocate oysters.

“We’ve had mortality due to freshwater in the past,” said Michael, “but we won’t know the extent of the mortality until we conduct the surveys.” DNR expects to finish surveying oyster reefs by the end of the year.

An influx of fresh water isn’t always bad for oysters; it could provide a bit of relief from disease. In an interview with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Ryan Carnegie, a research associate professor at VIMS, noted, “MSX disease may largely be purged from Chesapeake Bay oyster populations as the parasite Haplosporidium nelsoni cannot withstand salinities below 10 [parts per thousand].”

“But,” he continued, “because of these low salinities large numbers of oysters in upriver beds in places like the James River have died.”

Blue crabs, on the other hand, can move to where conditions are more favorable, although they can tolerate fresher water. In the Bay itself, they seem to be staying farther south and at the edges, where salinity and dissolved oxygen levels are higher. In the rivers, DNR trawls show upriver sites containing more crabs, which is normal for this time of year.

It won’t be until this year’s winter dredge survey is complete in Maryland and Virginia that researchers will be able to determine impacts of the unusually wet year on the blue crab population. Last year’s survey found fewer adults but more juveniles that the previous year. Overall, the population was still large enough to not be considered depleted.

Finfish are moving to new places.

Just like crabs, when salinity changes, finfish can move to areas better suited for them. This means salt-loving fish move south, and freshwater fish begin to appear in areas they aren’t normally seen.

Researchers at VIMS are noting these changes already. “Though overall abundance doesn’t appear to be affected, juvenile striped bass are spread out over a much wider area than usual,” said survey manager Brian Gallagher. He attributes their shift into down-Bay waters to the drop in salinity as a result of this year's abundance of freshwater flow to the Bay.

Another fish that could be taking advantage of lower salinity is the blue catfish. According to Vaskar Nepal, a Ph.D. student at VIMS studying the invasive fish, wet months may allow blue catfish to expand further into the Bay due to lower salinity levels.

“During high freshwater flows, the upper layers [of the Bay] are actually fresher than the deeper layers simply because freshwater is lighter than salt water,” said Nepal. Therefore, areas that are generally off-limits for blue catfish may become places they can use for migration.

Underwater grasses will decline, but this year will test their overall resilience.

The high flows in the Susquehanna have sent much more fresh water, and accompanying sediment and nutrient pollution, over the Bay’s underwater grasses, also called submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV). This could rip out grasses, smother them with sediment, cloud the water so they can’t get sunlight or lead to algal blooms which could also block out light.

Luckily, the damage doesn't seem too extensive, although we won’t know the full impact until the aerial surveys are completed in Maryland and Virginia. Brooke Landry, a biologist with DNR, noted how the grasses at the mouth of the Susquehanna River, in an area called the Susquehanna Flats, have been holding up. “After the July [rain] event, the water over the SAV bed was clear. You could see grasses in eight feet of water and fish swimming around as well.” Although there was some impact on the grasses, it was primarily at the edge of the bed where those grasses were buffering the sediment from reaching the grasses in the inner bed.

In the south, the news has not been as good. “We believe, and we’re not sure how this will play out until next year, that the eelgrasses in the York River seem to have disappeared,” says Robert Orth, professor of marine science at VIMS.

“We’ve had turbid conditions in the York before, but not with this level of fresh water.” Eelgrass needs salty, clear water to grow, so the lack of both could have led to their disappearance.

Along with the current beds staying in place, reproduction is another issue. Most southern grass species have already reproduced, but for some in the northern part of the Bay this is only happening now.

“A lot of times what happens when plants get stressed, if they're nearing reproductive timeframes, they hurry up and do it quickly,” said Landry. However, the opposite could happen as well. It takes a lot of energy for plants to reproduce, so if they are feeling stressed, they may skip it for the season.

In 2011, when Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee swept through the area and sent extra nutrients and sediment down the Bay, the grasses took a hit. Abundance of underwater grasses went from 79,664 acres to 57,964 acres, although they were already on a decline do to a particularly hot 2010.

“If it were a decade ago, I would have been much more concerned with the beds being wiped out,” said Landry.

Although optimistic, she still expects to see lower numbers next year. “Beds expand and contract all the time. Conditions need to be perfect for continual expansion, and nature’s not like that.”

Even in the lower Bay, where grass species rely much more on salinity, there is optimism. “I think we’re going to see in some areas less SAV than last year, which was the record year,” says Orth, “but I don’t think it’s going to be a total disaster.”

Gathering and analyzing data will be key to understanding how the Bay’s underwater grasses are doing. “We look acre by acre, segment by segment,” said Bruce Michael. “There are 92 Bay segments. We look at the amount of grasses in each.”

The dead zone may be smaller than anticipated.

At the beginning of the summer, scientists predicted the Chesapeake Bay would see a larger-than-average dead zone due to above-average winter and spring Susquehanna River flows to the Bay.

High flows play an important role in determining the size of dead zones. As rainwater travels to waterways, it picks up nutrients which fuel algal blooms. When blooms die and decompose, the resulting areas of little to no dissolved oxygen are called dead zones because they can suffocate underwater plants and animals.

This summer’s additional rains came as storms, with stronger winds and more overcast days. Strong, frequent winds have helped to mix up the Bay’s water and inhibit algae’s ability to thrive.

“Algae like sunny, calm weather,” said Michael. “Because this summer has been so cloudy and overcast, we haven’t seen a lot of algal blooms this year.” In fact, DNR’s monitoring cruise observed the best ever hypoxia conditions (meaning the smallest amount) in the Bay for the end of July, and near average conditions for August.

One thing we’ll have to watch over the coming months is rain and water flows, because even though this summer’s dead zone will likely be smaller than forecasted, those extra nutrients won’t all disappear over the winter and could set us up for a larger dead zone next year.

Measuring the impacts

The Chesapeake Bay is a vast, multifaceted estuary with many parts that respond differently to this summer’s extreme weather. Right now, we can only make educated guesses about the effect of 2018 weather events on Bay health based on past events and current observations. It won’t be until later this year that we have a better ides of the full impact on the Bay.

To fully understand these potentially wide-reaching impacts, the Chesapeake Bay Program’s water quality monitoring partnership—and it’s established history of data—is more important than ever. “The monitoring results provide our community with the information needed to assess how the Bay reacts to storms and other weather events," said Peter Tango, monitoring coordinator for the Chesapeake Bay Program. "We also gain a greater understanding on our progress in improving water quality and habitat health as efforts are made to reduce nutrients and sediment in our waterways related to watershed and Bay restoration efforts."

Stay tuned as we gather and interpret these results.

Comments

I am a collector of driftwood, is there any I could find along the conowingo , or where the dam empties out

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories