Many regions, one Chesapeake

The diverse landscapes of the watershed all flow together into the Bay

The Chesapeake Bay watershed covers a total of 64,000 square miles, all of which eventually drain into the Bay. This region, home to 18 million people, includes 206 counties, 1,800 local governments, parts of six states and the District of Columbia. Within this huge area is incredible diversity: farms, cities, wetlands, forests, fresh water, salt water and everything in between. While each of the regions of the watershed is unique, they are all a part of the larger whole, and actions taken hundreds of miles upstream can still affect the Bay. Learn more about the eight regions of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

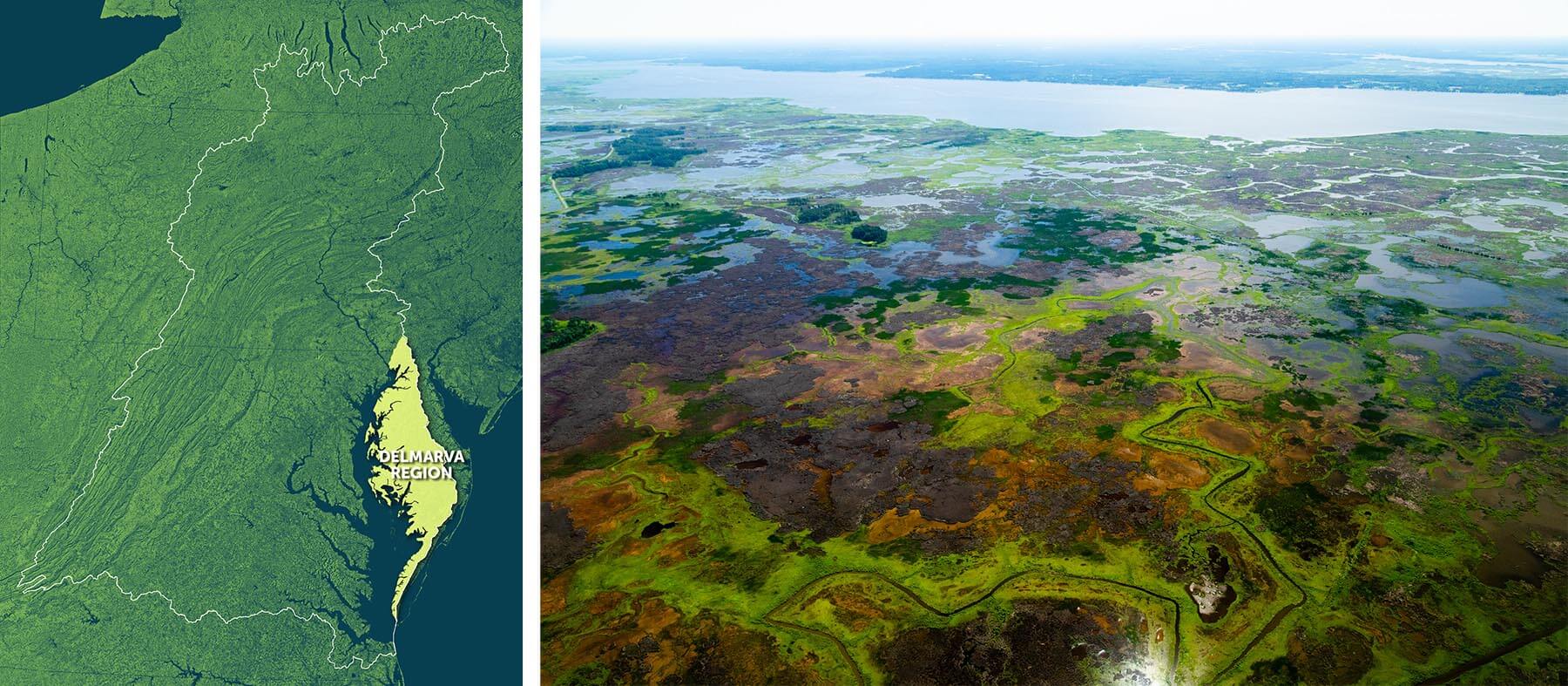

Delmarva Region

Fishing Bay Wildlife Management Area in Dorchester County, Md. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

Fishing Bay Wildlife Management Area in Dorchester County, Md. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Delmarva region is a peninsula that includes part of Delaware and the eastern shores of Virginia and Maryland. The region's main rivers include the Chester, Sassafras, Choptank, Miles, Wye, Nanticoke, Marshyhope and Pocomoke. The Choptank is home to two of the tributaries targeted by the Bay Program for oyster restoration. The area is one of the largest restoration projects in the world. The region is heavily agricultural, and farmers, nonprofits and government agencies are working together to come up with solutions to reduce pollution, from innovative new practices to old-school buffers. Much of Delmarva is low-lying, making it vulnerable to sea-level rise. The region’s shorelines and islands are also threatened by erosion. Living shorelines and artificial reefs are being utilized to try to protect shorelines, as well as provide habitat.

Delmarva visitors can explore sites along the Nanticoke, which is home to some of Maryland’s most pristine wetlands. The region is also home to the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, a 125 mile stretch where visitors can explore the history of the Underground Railroad and learn more about Tubman, who was born in the region.

Susquehanna Region

Painted Goat Farm in Otsego County, N.Y. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

Painted Goat Farm in Otsego County, N.Y. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

Covering more than 27,000 square miles of Pennsylvania, New York and Maryland, the Susquehanna region makes up 43 percent of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The majority of the region falls in Pennsylvania, and it accounts for more than half of the state’s land area. The region’s more than 50,000 miles of rivers and streams supply half of the Chesapeake Bay’s fresh water. Much of this area is forested, providing cleaner air and water as well as wildlife habitat. Native brook trout, which are rarely found in areas with even small amounts of development, are just one of the species that benefit.

The Susquehanna offers beautiful scenery as it flows from Otsego Lake in New York to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Although hundreds of miles away, Otsego Lake faces many of the same challenges as the Bay, including invasive species and nutrient pollution. Otsego Lake is also the starting point for the General Clinton Canoe Regatta, an annual 70-mile canoe race along the northern stretch of the river.

Potomac Region

The Anacostia River near Kenilworth Park in Washington, D.C. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Anacostia River near Kenilworth Park in Washington, D.C. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Potomac River watershed includes Washington, D.C., and parts of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia. The region is home to more than six million people, one-third of the total Chesapeake watershed population. The river itself, which is 383 miles long, has made incredible progress in the past decade, improving from a “D” to a “B” on its river report card. The progress is due in part to big improvements in wastewater management throughout the region.

Because it flows through Washington, D.C., the Potomac River is known as the “Nation’s River.” From its headwaters at Fairfax Stone in West Virginia to its mouth at Point Lookout in Maryland, the river is full of historic sights important to this nation’s history. One of its main tributaries, the Anacostia, is known by the less-grand nickname “Forgotten River.” Despite this, the river is making a comeback, both in terms of its health and its recognition, and there are many places to explore, boat, fish and play along its banks.

Rappahannock Region

The Rappahannock River in Middlesex County, Va. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Rappahannock River in Middlesex County, Va. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Rappahannock region covers 2,700 square miles of Virginia. At 195 miles, the river is the longest free-flowing—meaning unobstructed by dams—river in the Chesapeake. The lack of dams makes the Rappahannock a valuable habitat for shad, which need to migrate upstream to spawn. Historically the most valuable finfish fishery in the Chesapeake, shad have been threatened by pollution, overfishing and habitat loss.

The Rappahannock spans a variety of landscapes, from mountains to metropolis. Many people are moving to the region, which is home to three of the four most populated localities in Virginia, and you can see the combination of mountains, agricultural lands and cities from the sky. In order to feed the region, and give a new spin to an old industry, aquaculture operations are popping up around the Rappahannock—and the rest of tidal Virginian. Oyster farming is the most rapidly developing sector of Virginia shellfish aquaculture, and the state is the number one oyster producer on the East Coast.

Western Shore Region

The Patapsco River and Inner Harbor in Baltimore. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Patapsco River and Inner Harbor in Baltimore. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Western Shore region in Maryland includes the Patapsco River, Back River, Severn River, South River and Magothy River, as well as major cities like Baltimore and Annapolis. Between these two cities, the region has a significant amount of developed lands, but outside of the cities much of the region is agricultural.

Communities on the Western Shore have made significant progress in incorporating green infrastructure, which can help to trap and filter stormwater while making communities more beautiful and resilient. Nonprofit organizations in Annapolis, Maryland, teamed up to restore local waterways heavily impacted by surrounding roads and buildings, while Baltimore is using innovative financing techniques helping to fund green infrastructure projects.

James Region

Natural Bridge State Park in Rockbridge County, Va. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

Natural Bridge State Park in Rockbridge County, Va. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The James River watershed covers one-fourth of Virginia, an area of 10,000 square miles. At 340 miles, the James is the longest river in Virginia, and the watershed includes more than 15,000 miles of rivers and streams. The region is home to the eastern seaboard’s largest bald eagle roosting area. Bald eagle populations throughout the watershed have made a significant recovery since the ban of DDT, a pesticide that led to compromised eagle eggs.

The James River is also a popular place for dolphin sightings. In order to learn more about these creatures, like when they visit the Bay, where they go and why, the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science started DolphinWatch. This citizen science project tracks the date and location of dolphin sightings and helps researchers understand dolphin behavior in the Bay.

Patuxent Region

The Patuxent River in Prince George's County, Md. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Patuxent River in Prince George's County, Md. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Patuxent River watershed covers 900 square miles in Maryland and parts of seven counties. Thirty-two percent of the region is developed, which helps accommodate increasing populations but can also increase polluted runoff. Runoff and wastewater have both impacted water quality in the area, which has led to a decline in oyster populations that have historically been vital to the region’s economy.

Each year, former Maryland senator Bernie Fowler measures the Patuxent River’s water clarity in a unique and intuitive way: by the visibility of his sneakers. Since 1988, Fowler has hosted the annual Wade-In on the river. Clad in his signature white sneakers, jean overalls and cowboy hat, Fowler walks into the river until he can no longer see his shoes, then measures the water depth to create his “sneaker index.”

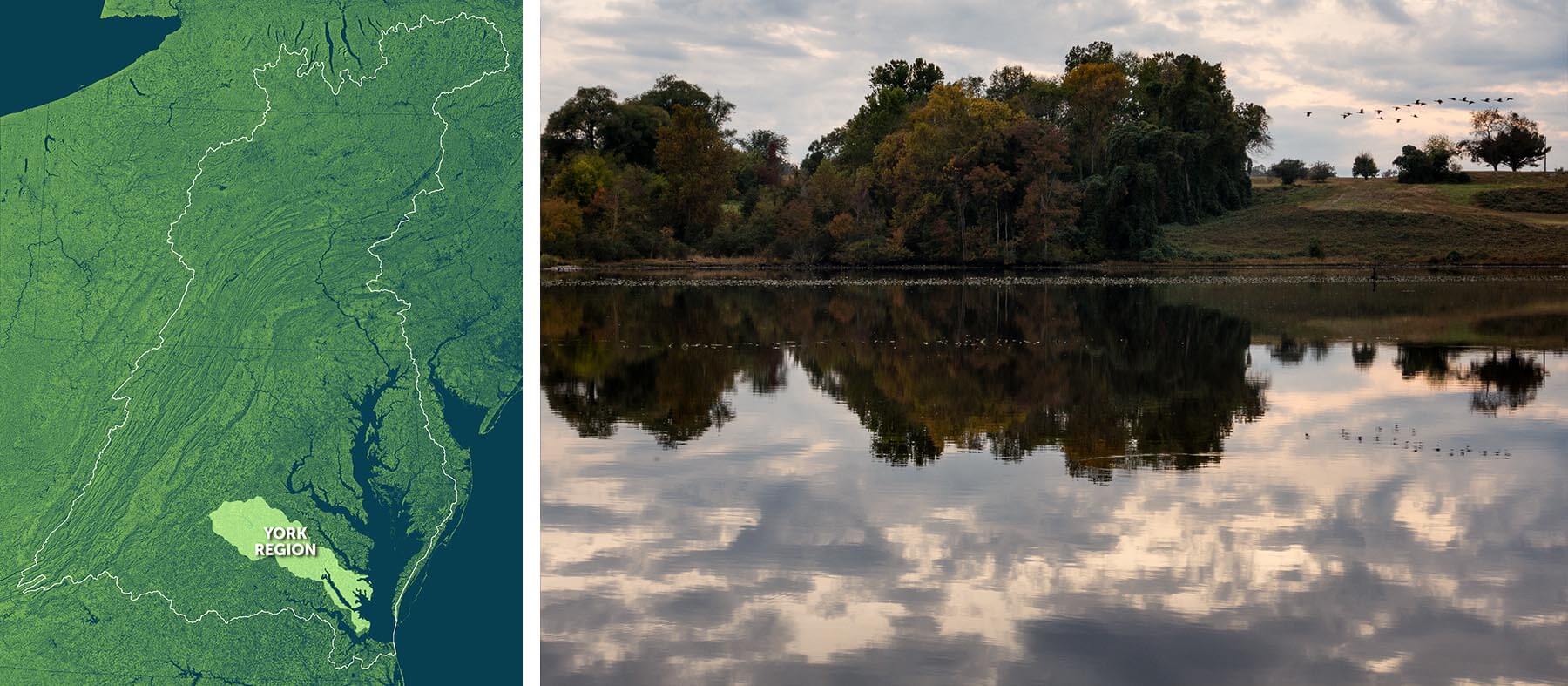

York Region

The Mattaponi River in Frederick County, Va. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The Mattaponi River in Frederick County, Va. (Map by Dave Yayac, photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program)

The York River watershed covers 2,600 square miles of Virginia, from the Blue Ridge Mountains to the Piedmont to the Bay. More than 370,000 people call this area home, as do important species like shad, blue crabs and the endangered Atlantic sturgeon.

The York region home to the Watermen’s Museum, which offers an in-depth look into the role of watermen in the Chesapeake Bay, from pre-colonial times to today. The region is also known for its efforts to restore shad to the region. For example, the Pamunkey tribe has operated a shad hatchery in the region since 1918. The Pamunkey River shad runs in the York region are some of the healthiest in the Chesapeake.

Now that you know more about the regions that make up the Chesapeake Bay watershed, learn what you can do to make a positive difference for your region and for the Bay.

Comments

I love this. I have lived in several of the regions, each for many years. I would love to be able to see the maps much larger and see more detail

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories